"A wonderful online resource..a series

of outstandingly good and carefully researched articles on the history of the

area" - Who Do You Think You Are magazine?

Here

are our pages on local Grangetown history. We hope to add more features

and would welcome any stories, articles, memories or photographs. Please

email

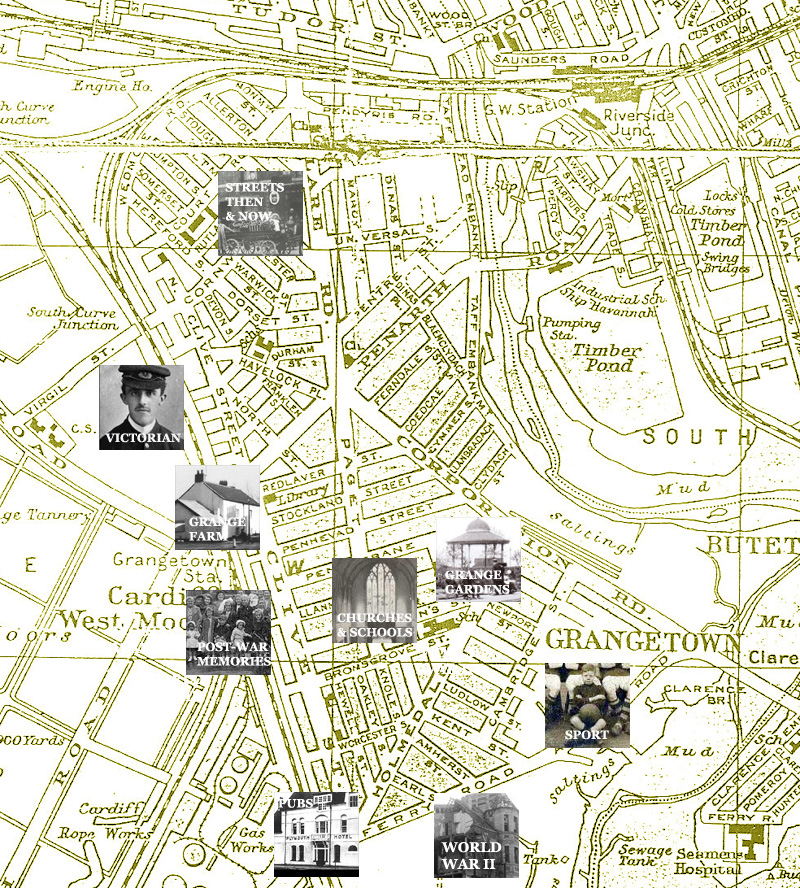

Here is Grangetown

history from the early days to the area's growth in the Victorian age

to the first few decades of the 20th century.

Thanks to Peter Ranson and the Grangetown Local History Society - www.grangetownhistory.co.uk - for

their help, especially with photographs and also to those members and others

at home and abroad who have added memories and stories. If there are any copyright

issues we are unaware of, please let us know and we will gladly give a credit/amend

etc.

|

Go

to 1930s and Second World War

Post-war

1950s and schools memories

Sport

and Transport and the history of Grange Gardens and local recreation

Churches

and schools and also Pubs

and clubs and

the history Of Grange Farm.

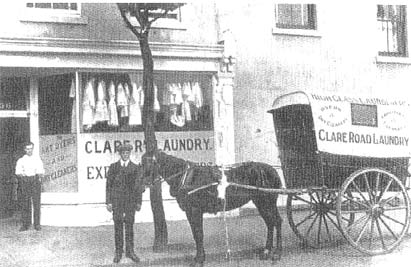

Grangetown industry - from iron, rope, gas to cigars

Victorian Grangetown politicians

Streets origins

and Census (in progress)

Photos of Grangetown then and now

Go

to Grangetown World War I Centenary - 1914-2014, Online Memorial

'Our

grange near the town of Kaerdiff'

Grange Farm in the 1890s, in the 1970s and today.

Grangetown's oldest surviving building - Grange Farm - is a reminder that

both the building and the area which took its name can be traced back 800 years

to medieval times.

The Cistercian monks of Margam Abbey (near modern day Port Talbot) established

a grange to farm the land in the early 13th century, off what is modern day

Clive Street. It was an outpost, and legend has it that they were sent there

as penance for drinking and gambling! Moor Grange was reputedly built at some

time between 1193 and 1218 and ran to 100 acres. The monks had been granted

land at Margam in the mid 12th century, with the abbey founded with the help

of Robert, son of King Henry I and by the end of the century Henry Bishop of

Llandaff had granted to the abbey all land nearby "in more de Kardif," in return

for an annual rent.

According to a short history of Grange Farm, put together from local records

in the 1940s by J Cleary Martin, details of the land emerge again in 1329 in

the reign of Edward III. Noblemen sitting at a court at Cardiff Castle heard

a land dispute involving the Abbot of Margam and the recently departed Lord

of Cardiff, Gilbert de Clare, killed at Bannockburn. The abbot had a dispute

with Clare over land at Kenfig (near modern day Bridgend) but the judgement

in the monks' favour also mentions "the grange on the moor near Kardif."

The Grange of Luquyth (Leckwith) by the end of the 15th century had 400 sheep

and 100 cattle and the abbey leased out the farm through Jasper Tudor (Henry

VII's brother) to Griffith ap Meuric. The records also showed 7s 1d was paid

for taking "17 loads of hay from the abbot's Grange" to the lord in

Cardiff.

Lewis ap Richard was the last farmer to lease from the abbey. His agreement

from the monks stated - "know ye that we have delivered to Lewis ap Richard,

esquire, our grange near the town of Kaerdiff, commonly called More Grange,

with the end term of 90 years. " £6 13s and 4d was payable on the feast

of the Anunciation, along with 4s a year to the Bishop of Llandaff and two acres

of hay to the abbot. Lewis was also responsible "to suitably repair and

maintain" the grange, house, sea walls, weirs, ditches and fences.

But with the dissolution of the monastries by Henry VIII, Abbot John of Margam

was pensioned off and the farm passed to the Lewis family (of Van, Caerphilly)

in 1537. In 1547, Edward Llewelyns was farmer with the same rent Lewis ap Richard

had paid. By 1595, rent had dropped to 44 shillings a year, showing the farm

had declined somewhat - "messuage (house and outbuildings), one barn,

one parcel of land, meadow and pasture called the Graing de Moore."

By 1638, "the manor land they called the Grange Marshes," was 300

acres, each with a yearly value of 4d. It was "bounded by the higher lands

of Penarth in the west, the Severne shore on the south, and the River Tave on

the east, and the common lands of Leckwith in the north."

Forward a couple of centuries and the land passes onto the Earl of Plymouth

and a long association with one family. The Morgans started running the farm

for the Plymouth estate in about 1835.

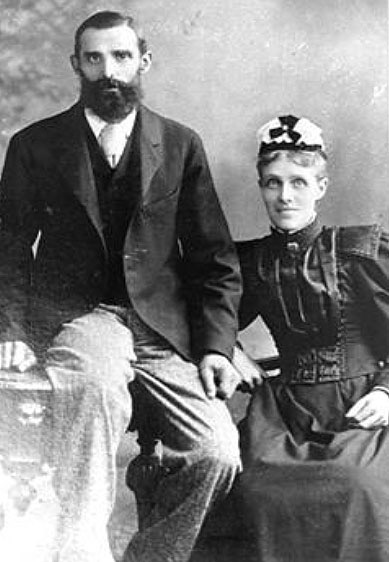

By 1881, we find the 120-acre dairy farm being run by the Morgan's third daughter

Ann and husband Samuel Burford. The Grange Dairy provided milk locally, while

the farm also kept animals and a coal business. Not long before her death, Doris

Burford, who still lived at the farm in 1987 recalled her 78 years born and

bred there. As a girl, she got up at 4am to start the milk round, first in a

horse and cart, eventually in a van. "It used to be dark getting the horse out

of the stable - I was a bit frightened," she recalled to the Echo. "We

used to sell the milk straight from the shed - now a garage - until the rules

came in that it had to be pasteurised."

"Everyone would come to the house - it was the only one for miles. It

used to be the life and soul of the place," said Doris. The farm was taken

over by her nephew and at the turn of the century was bought by new owners,

who have painstakingly restored it and discovered some more original features

in recent years.

You can read a fuller account here in

our History Of Grange Farm.

Despite the terraced streets built on its old land,

the farm building still survives today, with some original features inside.

It is Grade II listed. The Victorian library building, preserved as converted

flats in 2008, is a pleasant neighbour.

Full steam ahead for king coal and

Cardiff

Cardiff was a fairly insignificant market town until the 19th century. Its

population was barely 1,900 - and at the start of the industrial revolution,

it was still dwarfed by the iron town of Merthyr Tydfil and copper town Swansea.

Under successive Marquesses of Bute, who inherited estates and land, Cardiff's

importance grew as its docks and railways were built and it became the world's

pre-eminent port for coal for steam ships. The population rapidly grew to 165,000

by 1901, with 20,000 new homes built in the last two decades of the Victorian

age.

It was nearly "Clivetown"

The name "Grangetown" was bestowed by Baroness Harriet Windsor-Clive, daughter

of the Earl of Plymouth, the owner of Grange Farm and other local land from

the Plymouth estates on which much of the later suburb was developed. In 1857,

it had been suggested that the new area be named "Clivetown" after the family

name of her late husband Robert Clive, the MP and son of "Clive of India."

But the Baroness would have none of it. She wrote: "The subject of a

name for the new Town we may now expect to see spring up on the Grange and he

(son Robert Windsor-Clive) is more disposed that it should bear the name of

the locality rather than that of 'Clive'. 'Grangetown'would be very suitable

for various reasons and is I think the best - the name of 'Clive'may appear

for the principal street."

Early industry

In the first few decades of the 19th century,

Grangetown would have been a few houses but it also had pockets of industry,

which grew up in the late 1850s and 1860s. These include a tannery,

a rope works, brick yard, gas works and a short-lived iron works. Others included

a candle works. Later, the Freeman's cigar factory became a significant employer

of women. You can read about all these industries here.

First came the railway, then rapid growth

The railway was a predecessor of today's suburb and along with the river Taff

defines its boundary. Some say this enclosure helps modern Grangetown retain

something of its old "village" atmosphere.

The village of Lower Grangetown was first to grow (with Clive Street,

Holmesdale Street, Kent Street, Worcester St, Amherst, Bromsgrove, Knole, Sevenoaks

and Hewell Streets) and was well established between the 1860s and 1880s. The

Grange National School opened in 1864. A report in the Cardiff Times in

1865 found it was not perfect in places. "The police here, with their inspector

from Llandaff, seem to be most active in compelling the keepers of pigs and donkeys

to look to the state of their dwellings, where it appears from the police reports,

pigs, donkeys, cows, children and chickens have been in the habit of messing together,

in one dwelling, and even in the same room. The proprietors in some cases are

finishing their houses; others are pulling theirs down."

Auctioneer Thomas Clarke said he first knew Grangetown in 1859 "when it was

a dismal swamp and morass, given even the village missionary, the water wagtail

and the postman who passed it on his way to the ferry." The scene, however,

by 1873 offered a great contrast and he argued it was "capable of great

development in the future."

Auctioneer Thomas Clarke said he first knew Grangetown in 1859 "when it was

a dismal swamp and morass, given even the village missionary, the water wagtail

and the postman who passed it on his way to the ferry." The scene, however,

by 1873 offered a great contrast and he argued it was "capable of great

development in the future."

An Estate Act of 1857 had allowed Lady Windsor to mortgage farmland to raise

money for new roads and what was regarded as the city's best drainage and sewage

system. Long leases on land were sold to a patchwork of builders and speculators

to develop new housing for workers. There was originally hope of developing

Grangetown as an industrial area, with workers living close by, but this never

really took off and it became a commuter area for the Docks. M J Daunton's study

of the Windsor records between 1857 and 1875 found that Grangetown's progress

was hit by a city-wide housing slump at one point, with the developments taking

a long time to break even, with suitable returns for the builders and landlords.

He said it was piecemeal progress involving "many hands over many years." Between

1873-74, he lists 10 different builders in Holmesdale Street and Amherst Street

alone.

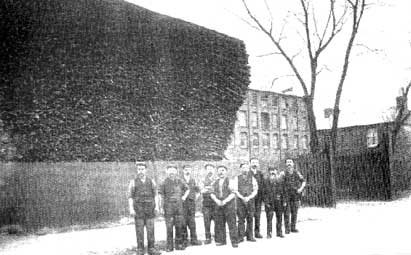

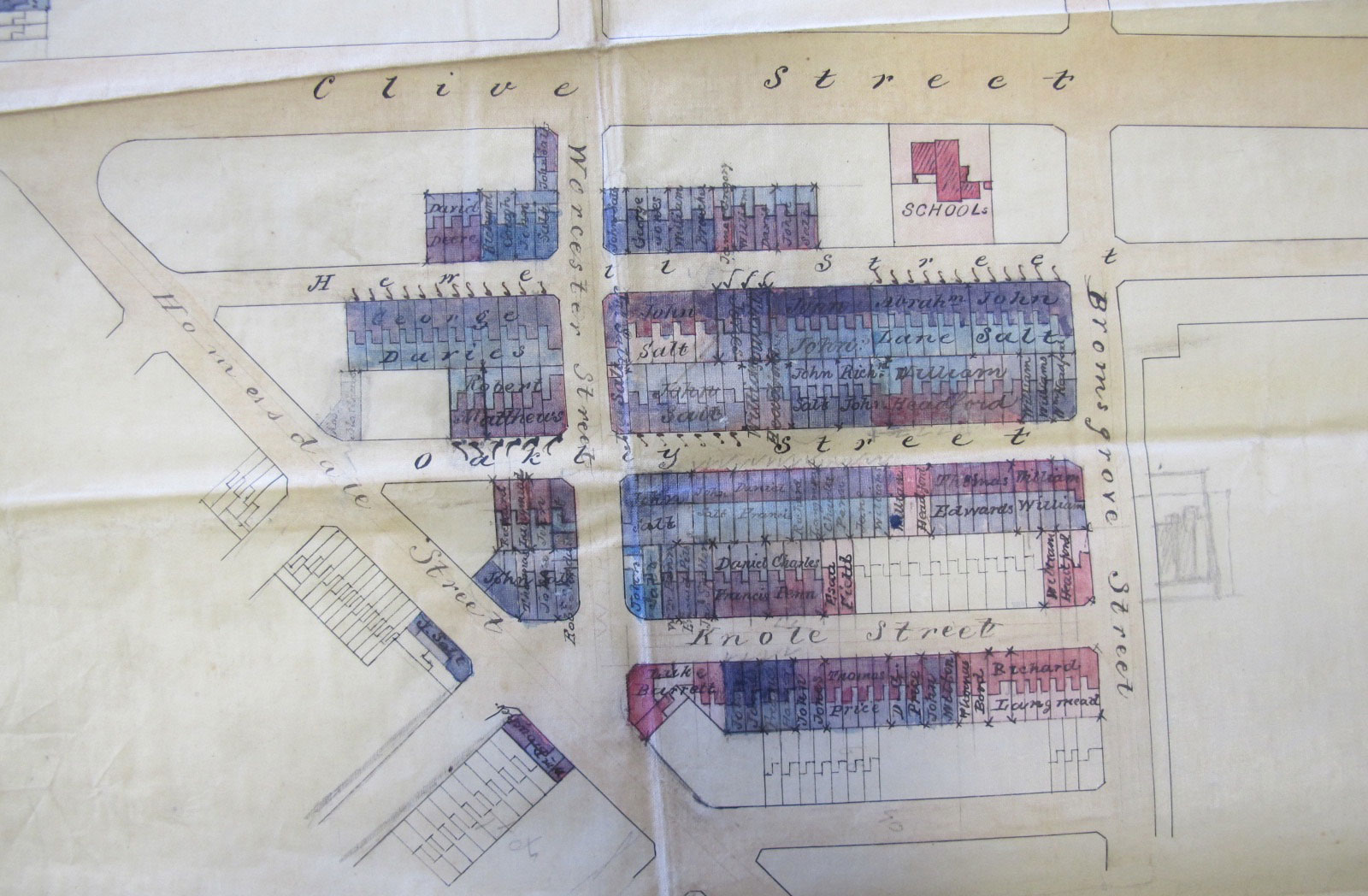

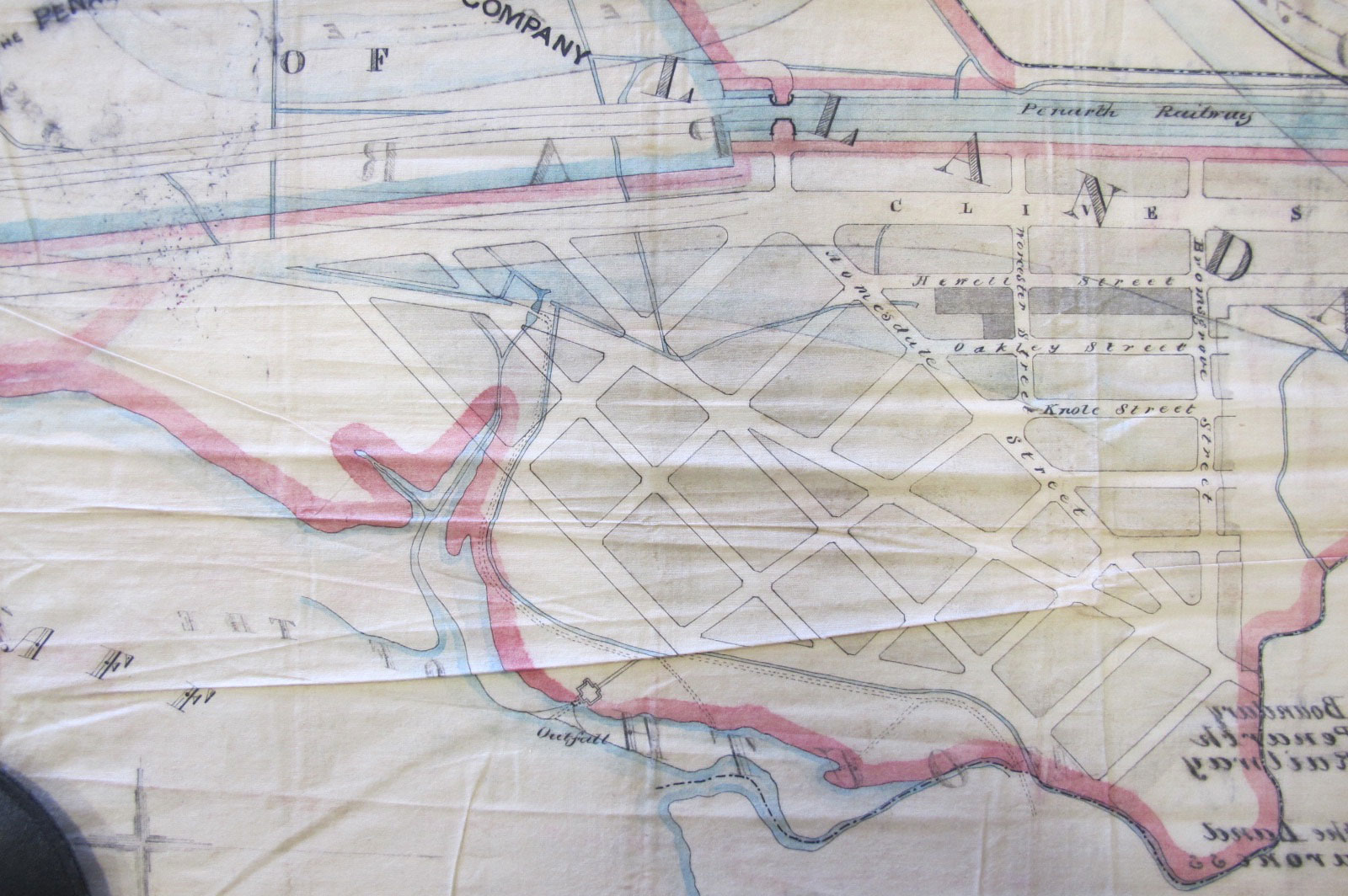

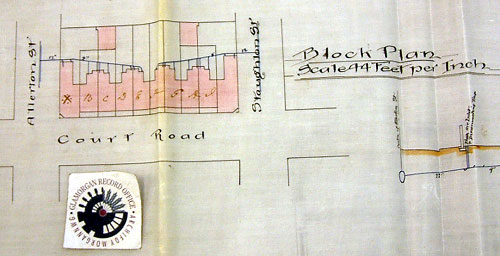

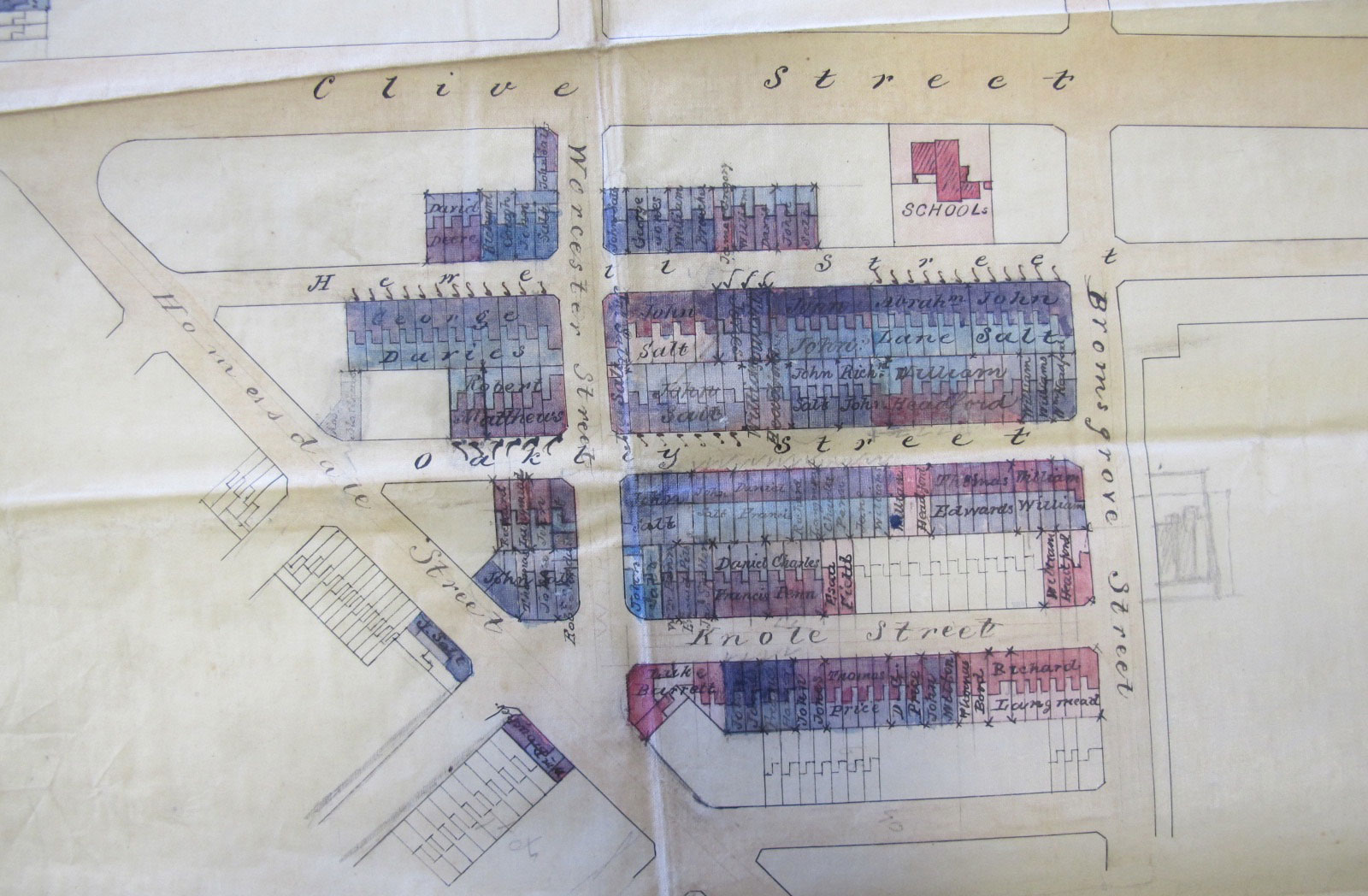

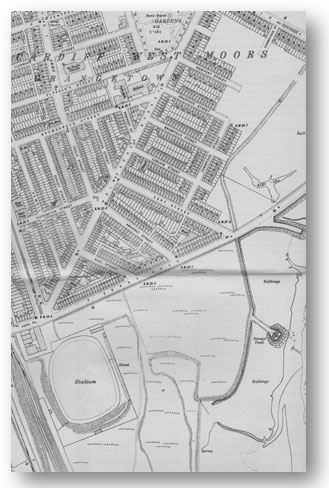

Grangetown Local History society member Ray Noyes has published a book Victorian Grangetown which looks at the planning, engineering and building of Lower Grangetown. Above is an early sketch map of Lower Grange - and you can see the names of

the different builders for the houses, including John Salt quite prominent.

He left £3,000 when he died in 1876, aged 45. He lived in a house, Tower

Grange, "near the bridge" and Grangetown iron works. There's also

builders like Abraham Lane (1826-1870). Click image for full size.

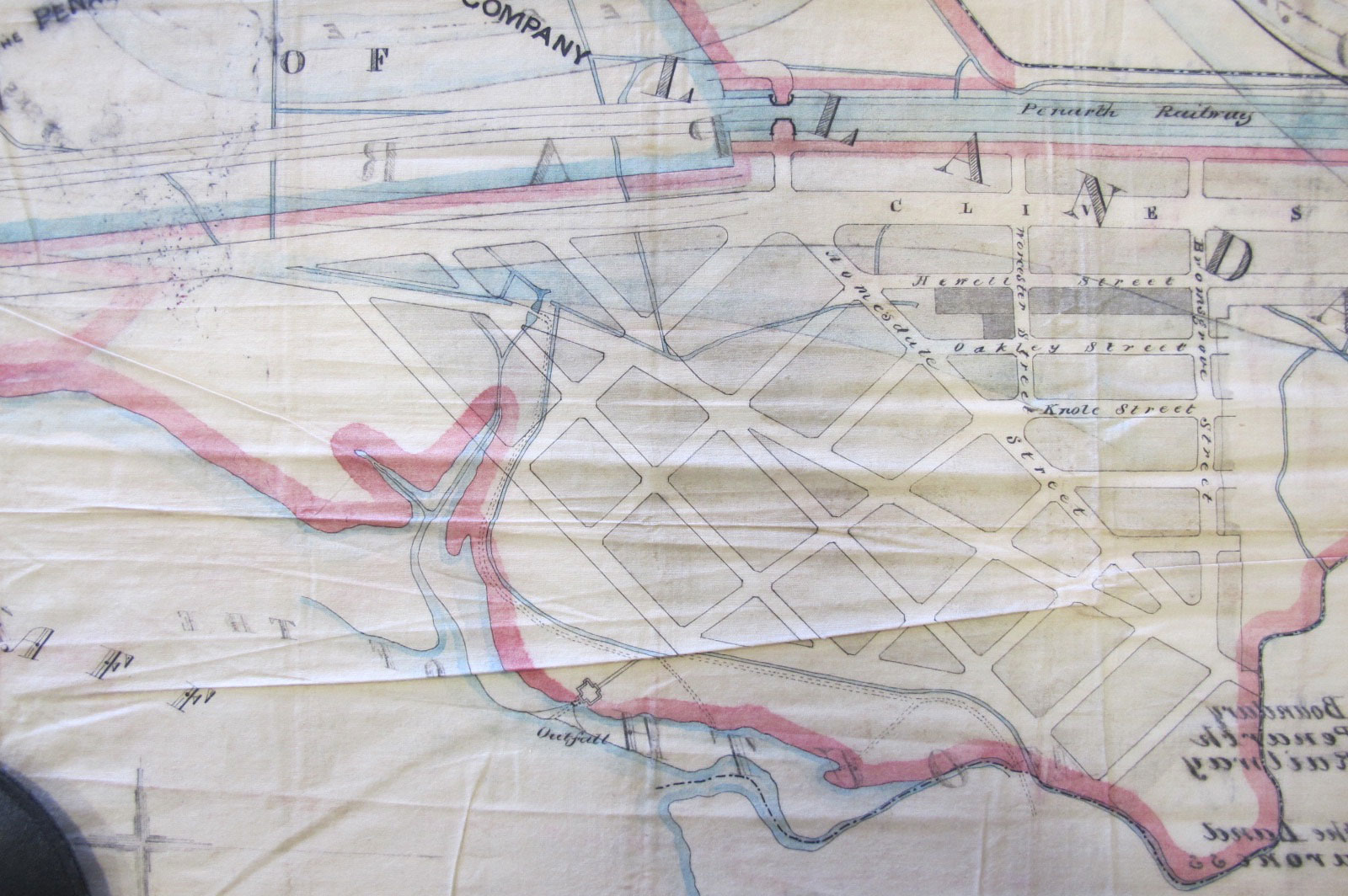

This is interesting because it shows early plans to build streets beyond

Ferry Road and towards the foreshore (to the bottom left). The biggest problems

facing builders in Grangetown were flooding and the marshy land - so these streets

were not developed. Click image for full size.

This map from the 1870s shows the baptist church in Clive Street and off

Penarth Road, significantly the brick works - between modern Redlaver Street

and North Street. The ground was perfect for "marl" clay. At its height

in the late 1860s, the works turned out 1.5m bricks a year. Another brick works

was located between Penarth Road and modern day Clare Road - in the Taff Mead

area. Click image for full size.

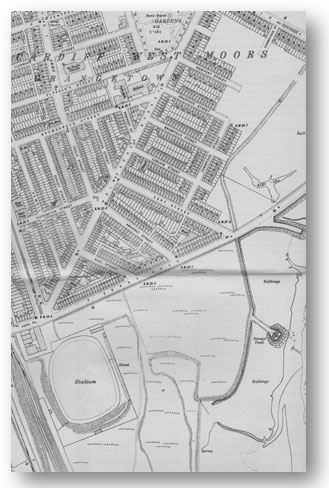

Upper Grangetown - known for years too as Saltmead - was slower to develop.

A few streets, chiefly North Street and Thomas Street off Penarth Road, were

built by the start of the 1860s and home to many Irish immigrants. The majority

of streets, off Cornwall Street and North Clive Street and close to the railway,

were constructed for the thousands of migrant workers in the late 1880s and

1890s, as Cardiff expanded. For years, what is now Saltmead was just moorland.

The Cardiff Times reported Canton residents petitioning in 1865 for a

new road to link where Baroness Windsor's new road ended at North Clive Street,

due to the difficulties in walking the direct route across the moor in winter

- they had to walk back home from the docks via the town centre. "It was

very unpleasant now to go to Grangetown across the moors and working people

and their operatives were driven to Roath instead," said the rector of

Canton, Rev Vincent Soulez.

There was pockets of poverty too, already by the mid to late 1860s. In 1867

in the town's poor relief books, Bridget Foley, 32, with two children, was described

as "destitute" and received four shillings and five pence a week, as well as

food and milk; Thomas Allen, 40, was widower and father-of-four who was too

ill to work - as well as seven shillings a week in relief, he received food,

meat and 14 shillings to meet funeral expenses; Mary Collins, 34, had been deserted

with five children and was given five shillings a week.

These two distinct areas of Grangetown were linked by Clive Street and crossed

by Penarth Road. The old Moors Road (later Clare and Corporation Roads), ran

parallel to the Taff although not all the way to Butetown in the mid 1880s.

In 1875, Grangetown became a Cardiff suburb,

although there were still fields separating it from the town centre. The two

parts of Grange were still distinct - Saltmead in the north, named after the

salty marshland; and lower Grange to the south.

Grangetown, prone to flooding

The Ely burst its banks after continual rain one Thursday morning on July 15th 1875 causing "widespread devastation" in Canton and Upper Grangetown. The Cardiff Times reported it vividly and also underlined how semi-rural Grangetown still was at this time: "The Grange, principally occupied by working men and their families, is completely surrounded by water to the depths of at least four feet, the highway to Penarth at seven o'clock in the evening being only passable to vehicles and horsemen. On the right of the highway the large field extending northward to the Great Western Railway resembles an inland lake, varying in depth from 4-7ft, and the water is just beginning to overflow the roadway opposite to the Grange Hotel.

"The streets which seem to be in imminent danger of being undermined by the swiftly rising waters are Thomas and Rosemary Street. The houses appear to be toppling over. Most of the furniture has been removed from the upper rooms, but a number of sick persons could not be removed in the ordinary way. A number of young men volunteered to procure a boat from the adjoining river Taff, and had succeeded in getting it partly on the way when darkness set in.

"Another group of men were cutting through the bank at the bottom of a field on the left side of the roadway, in order to admit if the water flowing into the Taff, In this they were successful to a considerable extent. About 30 head of cattle were saved from the adjoining field just before the water rushed through the gap in tremendous volume. The cutting of this gap reduced a portion of the large body of water from John's brick yard adjoining, and prevented the overflow on the other side from sweeping down in Lower Grangetown. The Taff Vale Railway, carried cross country by a high tip or embankment, has by its massive proportions saved this suburb from being at once twept away. Ascending this embankment and looking westward, the whole country for miles on each side of the Ely is under water.

"Floating hay-stacks thickly dot the surface, as well as hay-cocks of smaller size. Looking again to the eastward, through the cross streets of the Upper Grange, all kinds of vehicles are in requisition, getting loaded from the upper windows of the houses facing the Great Western Railway, partly dragging them and partly swimming. Some were fortunlate in reaching the main road, others, coming in contact with submerged goods in turning the corners of the streets, threw their goods into the foaming and eddying torrents - drivers, men and horses.

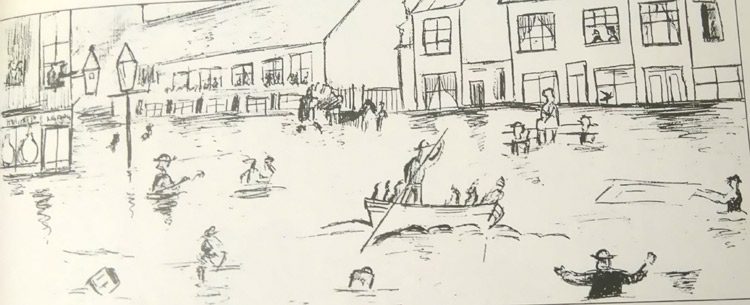

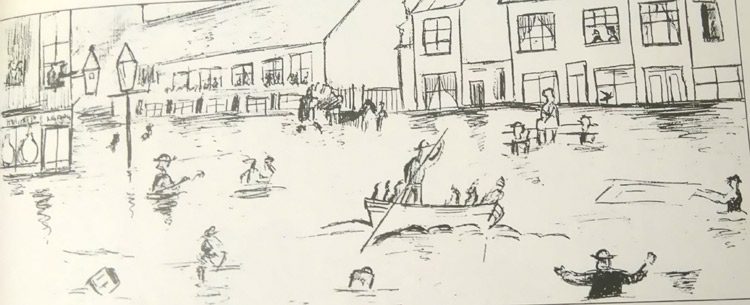

Hairdresser Sam Thomas drew this sketch of flooding in Ludlow Street in October 1883.

The report continued: "Willing hands were not wanting to cut the traces of the horses, and help the men, who otherwise would have been carried away and drowned. Scores of men we saw carrying their little ones towards Cardiff, and two men we noticed had what appeared to be aged females in their strong arms, carefully wrapped up in coverlets and blankets.

"Our reporter, who visited Upper Grange at 11pm, says the left side of the main roadway to Penarth opposite this place is completely submerged to an equal extent with the meadow, lands and fields on the opposite side, the water having increased fully three feet. The only drain pipe, said to be nearly nine inches in diameter, the entrance being opposite the Grange Hotel, is choked up with hay swept into it from the adjoining field."

The Cardiff Times concluded that there was "great anxiety" for the safety of the tenements "at the rear of the village" towards the Great Western Railway, as the "full force of the enormous weight of water is swaying them inwards towards the remaining buildings. Some people are reported missing, bnt it is expected that when the bustle is over they will be found."

Then on the evening of October 17th 1883, another high tide - with gale-force winds - saw water burst through the sea dyke opposite Kent Street, reaching a height of between 4ft and 7ft. A man rushed into the harvest thanksgiving service in Ludlow Street shouting "the flood is coming," Sam Thomas recalled. The preacher reportedly urged calm, before promptly fainting!

Flood water almost reached the first floors of houses, while people were wading up to their waists. Livestock was lost, with the whole area said to resemble a lake. Newspaper reports from the time give a long list of shopkeepers in Holmesdale Street who sustained losses - from shoemakers to grocers, nine pubs were affected including the landlord of The Plymouth (in Clive Street) who claimed he was down £200 after water flooded his cellar. Mr Edwards the grocer in Oakley Street lost £100 worth of stock. A third of homes lost their back walls between the streets. Those living in Kent Street were said to have suffered the greatest loss in terms of "spoilt furniture."

Schoolmaster James Buck - a small man - was carried to his home through the torrent by a visiting preacher - and much taller man - at Windsor baptist hall in Holmesdale Street.

Alfred Fish, a teenager during the flood, said Grangetown people were "somewhat superstitious" and some had read Mother Shepton's Prophetic Papers, which foretold the end of the world in 1881. "I remember as a lad how terrified the people were as they looked at the sky - black and streaked with white patches..in the early evening the water burst through the tide bank and rushed down the streets."

"I was caught up in the flood, about 12 houses from my home," he recalled as an old man in the 1950s. "I was soon up to my waist in water but presently a tall, strong woman named Mrs Perrott rushed into the middle of the street, picked me up and carried me into her house, took off my wet clothes and put me to bed. She was a customer of my mother (Sarah), who kept the grocery shop on the corner of Sevenoaks Street."

The waters had receded two days later when Lord and Lady Windsor visited to survey the damage.

The flood also hit the old Iron Room church, which was also holding its annual harvest festival service.

"We were assembled in church - a packed congregation - for the annual harvest thanksgiving service," recalled a bell-ringer 20 years later. "Presently we heard a commotion at the doors. A wild-eyed man had come to seek his daughter, for he verily believed that the whole populace of the Grange were in danger of their lives. Before anything could be done the water came percolating through the cracks in the flooring. Many sped from the building into the streets, where the water was rushing hither and thither and rising higher and higher as the tide rose."

"I myself and other youngsters amused ourselves by catching shrimps and minnows - a strange pastime in church. Meanwhile, the hymn For Those In Peril On The Sea was given out, and considering that by this time most of the adults in that congregation thought that they themselves were in dire peril, for the water was still rising steadily, they sang those thrilling words with a calmness that spoke of brave and trusting hearts within."

A few days later, Henry Marshall, a builder from Kent Street, wrote: "Having visited about 190 houses in Lower Grange, and the greatest portion of the houses in Upper Grange, I can bear testimony as to the disastrous results of the flood. The result is that the homes of the working men are to a great extent broken up, in most cases the best of the furniture being entirely spoiled. In many houses the piano or harmonium has gone to pieces, and in nearly every house the week's provisions and a large proportion of wearing apparel have been rendered useless, so that many families are left quite destitute, and are also suffering much from the cold and damp that follows such a flood, not having the means at their disposal to get coals etc, to dry their things and warm themselves."

Mr Marshall, along with local councillors, was one of those involved in raising awareness of the issues with town officials. Afterwards, damage was estimated at around £3,000 while £540 was collected in donations within a few days through public subscription, including from shipowners and other businessmen. There were also calls for the embankment and sea wall to be raised.

A system of clay banks or dykes (on the 1883 map above left) was not enough to solve the problem when either the River Taff or Ely rose to exceptional heights at high tide. It would be a century before the flood defences were adequate - while the building of the Cardiff Bay Barrage also helped reduce major incidents.

The biggest spurt in building came in the 1880s and 1890s and by 1901, the

suburb had a population of 17,000 - effectively the same as it is today.

The city's most prominent and grandest builders of the period were Grangetown-based,

E Turner and Sons in Havelock Place. As well as homes, schools and churches

across Cardiff, they were responsible for City Hall and Civic Centre. The company

remained there until 1993, when they moved to Cathedral Road and the offices

and cottages were demolished for new housing.

|

1871-1878: Disease and distress

The

north of Grangetown in particular had strong Irish and Catholic links. The

census of 1871 for Thomas Street shows us a number of Irish immigrants,

who'd settled with their families, many of them labourers with work in the

developing town. Typical is Thomas Fitzgerald, 45, a labourer with his wife

and seven children, all born locally. Neighbours include Ryans and Donovans.

There are also some brickmakers - which perhaps would tally with the brickworks

in Sloper Road. There's a pub at No 22 - The Penarth Dock run by Christopher

Griffith, 37, unusually, a Cardiff native, who lived there with his Swansea-born

wife and four young daughters. Another pub, the Grange Inn in Francis Terrace

first appears in the '61 census, run by a Daniel Francis. By 1871 it is

run by a widow from Durham. Living at 67 Francis Street (it was later renamed

Franklen Street in the 1890s, while there is also a Frances Street in Butetown,

just to confuse you!) are three families brought up in Cardiff and headed

by Irish-born labourers, John Pat Moricy, 45, his wife Mary and their six

children, aged from one to 20 - including 14-year-old Patrick, already a

labourer; John and Alice Cronin also had six children and James O'Brien

and his three young children. The

north of Grangetown in particular had strong Irish and Catholic links. The

census of 1871 for Thomas Street shows us a number of Irish immigrants,

who'd settled with their families, many of them labourers with work in the

developing town. Typical is Thomas Fitzgerald, 45, a labourer with his wife

and seven children, all born locally. Neighbours include Ryans and Donovans.

There are also some brickmakers - which perhaps would tally with the brickworks

in Sloper Road. There's a pub at No 22 - The Penarth Dock run by Christopher

Griffith, 37, unusually, a Cardiff native, who lived there with his Swansea-born

wife and four young daughters. Another pub, the Grange Inn in Francis Terrace

first appears in the '61 census, run by a Daniel Francis. By 1871 it is

run by a widow from Durham. Living at 67 Francis Street (it was later renamed

Franklen Street in the 1890s, while there is also a Frances Street in Butetown,

just to confuse you!) are three families brought up in Cardiff and headed

by Irish-born labourers, John Pat Moricy, 45, his wife Mary and their six

children, aged from one to 20 - including 14-year-old Patrick, already a

labourer; John and Alice Cronin also had six children and James O'Brien

and his three young children.

To give us an idea of some of the conditions is this report from September

1873. Eleven householders were summonsed to court for continual overcrowding

in their properties. Magistrates were told that the area was thickly populated

and typhoid was spreading, with seven cases reported recently. The Western

Mail report doesn't name the streets, only giving the area as Upper

Grangetown. The censuses puts the families in the Thomas Street, Havelock

Street and Rosemary Street areas. Thomas Donahue was found to have 18

people living in his three-bedroomed house, which was deemed fit for six.

Cornelius Driscoll had 11 in his similar-sized property. Michael Mahony,

his wife and five children shared their house with another seven people

- with the home only fit for half that number. The Western Mail reports

that the inspector when he visited Patrick Morris' house found three families,

of 18 people, with every room used as a bedroom. "The place was so foul

I could hardly enter it." Jeremiah Regan had a household of 14, including

his wife and eight children.

In November of that year, the Cardiff Sanitary Committee looked at Upper

Grangetown, where 59 cases of typhoid were reported, three of them fatal.

"This serious outbreak of a dreadful malady is attributed to the filthy

state of the habitation of the streets," reported the Mail, and it was

decided to apply to the Local Government Board to obtain powers of an

urban sanitary authority to make improvements. Grangetown was lying outside

Cardiff, and bringing it in as an official suburb would at least improve

conditions in terms of sewerage and drainage.

In 1878, with economic problems in the south Wales valleys acute - many

mines shut or on short time - and even Cardiff "suffering the pinch

of poverty after three years depression", charitable collections,

poor relief and soup kitchens were springing up for struggling working

families. The Western Mail noted however:

"It's somewhat remarkable, however, that no public movement

has been set on foot for the relief of the people of Grangetown. Here, the

inhabitants seem to be in greater want than in other parts of the borough.

The iron works having been closed, many out of work as a natural consequence,

and poverty is compelling a number of people to adopt all sorts of measures

for obtaining some kind of livelihood."

Later in the year, the paper found several people from Grangetown using

the soup kitchen set up on the corner of St Mary Street and Penarth Road..."their

wants being of an extreme character. A few casual inquiries in that neighbourhood

led the manager (of the soup kitchen, Theophilus Jones) to believe that

a vast amount of distress exists there."

I came across quite an interesting account of the end of the 19th century

in a St Patrick's parish magazine, dated from 1948. In it, C Sexton recalls

seeing in the new century at a special midnight mass. "We were all glad

to see the old century go. Times had been hard, there had been strikes

and unemployment and in the fall of 1899, we had started the South African

war that was to drag on for the next three years.

"In those days we had no electricity, very few houses had gas, the good

oil lamps, many of them with beautiful shades were in most use. I saw

the first electric car driven from the Clare Road sheds in 1901. In those

days, Solly Andrews' horse-driven tram cars and buses were the means of

transport...very few houses had baths and hot water."

The article also recalls as well as theatre and music hall in town, locally there were two concerts a year at St Patrick's school rooms - including an Irish concert on St Patrick's Day. Father Brady would also give a lantern lecture on his trips to Rome.

The writer also said it was still a few years before Grangetown library opened, and children relied on teacher Mrs Butler's own small collection of books, including favourites like Jules Verne.

Possibly proving that things come around, writing in 1948 - just after

the war years - it was noted: "One thing you do not see in these days,

but were seen frequently then were the number of drunken folk about at

closing time, Saturday nights and when a big football match was on." Shops

were also open until about 8pm every day, and Fridays and Saturdays untl

9, 10 or 11. Pubs were open at 6 or 7 in the morning, until 11pm at night

- midnight on Saturdays.

The old Thomas Street was demolished in late 1967 and new housing replaced

it. Madras Street disappeared to make way for St Patrick's School.

Some lived like pigs

in Grangetown- 145 years ago

"The police

here, with their inspector from Llandaff, seem to be most active

in compelling the keepers of pigs and donkeys to look to the state

of their dwellings, where it appears from the police reports, pigs,

donkeys, cows, children and chickens have been in the habit of messing

together, in one dwelling, and even in the same room. The proprietors

in some cases are finishing their houses; others are pulling theirs

down." Report from Grangetown, in the Cardiff Times, February

1866.

1871: A swindler passes through

He appears to be something of a rogue and a conman, but with every great

innovator and entrepreneur in Victorian Britain, there was also on opportunity

for deception by a host of shady characters. Prussian industrial chemist/engineer

Peter Kagenbusch, 56,passed through Grangetown in 1871 and took a widow

and a publican for a ride. He's listed in the census as lodging with mother-of-six

Rachel Watkin, whose two sons worked at the iron works. He had been introduced

to Mrs Watkin by the ironworks manager and it's almost certain the Grangetown

enterprise brought him down on doubtful business of peddling his patent

formula for puddling iron and expertise. His name crops up in bankruptcy

hearings in Liverpool, Leeds and London over the decades - and of doubtful

gold and silver prospecting scheme later in Scotland.

He certainly got around and could move quickly. Rachel contacted police

after Kagenbusch failed to return from Swansea where he had gone to get

money he owed her. He had borrowed £10 and owed another £10 in board and

lodging (money for her husband's funeral). He also owed money to Robert

Bryant, landlord of the Princess Royal. She followed him to Wolverhampton

and Newcastle in search of her money.

This all came out in a trial in 1873 in Middlesbrough, where Kagenbusch

was brought to justice. He had conned another publican out of money. He

would look for partners in his enterprise, while carrying evidence for

a string of "orders" (including one from Grange Town Iron Works) with

letters pleading for instant cash to keep the business alive by a colleague.

No orders existed and only samples of the product were ever sent out. Mrs Watkin's letter had been read out in court. "He had

presented himself in Grange Town as a gentleman of property...he's a bad

cruel man to defraud a poor widow of all I had in the world."

Kagenbusch was jailed for five years. But he later resumed other projects,

which left debt.

|

| 1881: Holmesdale Street - a snapshot

Holmesdale Street to many is the heart

of Grangetown, stretching from Grange Gardens to Ferry Road, with a network

of terraces off it, with shops and local schools. Back in 1881, who lived

there? The census in that year shows a Londoner, Edward Smith ran the Plymouth

Hotel at one end of the road with his wife and five children living there,

with three servants and a nurse employed. Living nearby were migrant workers

from Somerset, Gloucester and other parts - builders, two blacksmiths next

door to each other - one who had a game-keeper as the lodger, one Robert

Iles, 50. An iron moudler father and son, Thomas Gillard, one of two nearby

grocers (and another native of Somerset) - his neighbours, Fred Denham a

railway clerk and cab driver Alfred Gough were also from the west country.

There were also two green grocers, including Eleanor Wilkie, 60, a widow

and mother of two, whose teenage son John was a seaman. At No 48, there

was another grocer, Owen Jones, 70, a native of Aberaeron, while at No 78,

is the appropriately named William Hook, the butcher, 54, and yet another

from Somerset. George Blake ran the Lord Windsor pub at No 47 - which shut

a few years ago and is currently facing demolition. There are plenty of

dock labourers and coal trimmers (loading coal onto ships) of course. Showing

the distances people had travelled, is mariner David King, a native of Sydney,

Australia, who had moved from Cornwall with his wife and son, while having

a young daughter after their move to Cardiff.

An auction in 1883 saw houses in the street being sold for around £150. You

can find more on the 1881 Census under District 28b, Llandaff.

FEBRUARY 1886 - BURNING EFFIGIES OF POLICEMAN AND

HIS LADY

Something of a scandal amused Grangetown

residents, after a local policeman became infatuated with the wife of

the keeper of the York Club, near the Plymouth pub in Clive Street. The

woman in her 30s, and "very dressy" had been linked with a member of the

club and had left her husband. The policeman, who had served in Grangetown

for three or four years and was recently widowed, then became "much too

friendly" with the club keeper's wife. The Western Mail reported

that her estranged husband spoke with the constable, who insisted "he

would keep her in the defiance of everybody."" His infatuation led

to his neglect of duty, which led to an appearence before the watch committee

and his resignation. Some of the "young and fun-loving members of the

club" took to preparing to burn two effigies of the couple, whose dress

was paid for by the husband. The policeman had blue coat and hat and his

lover, with a "showy hat and huge feather." A procession marched

through lower and upper Grangtown, accompanied by tambourine, cow horn,

pans and kettles. A doggerel rhyme and shouts of "We'll hang old...on

a sour apple tree." They marched onto Tressilian Terrace, where the

couple now lived, and burnt the effigies on waste ground. The procession

was repeated on the following Monday evening, although this time a policeman

intervened and took the effigy of the wife. He was followed by a crowd

down St Mary Street, with the effigy under his arm, and inquiries made

"as to the nature of the offence committed by the prisoner, so tenderly

taken in charge."

|

Photos of Grangetown, with how those scenes

look today. Move your mouse over the old photos to see the change and click

here for more.

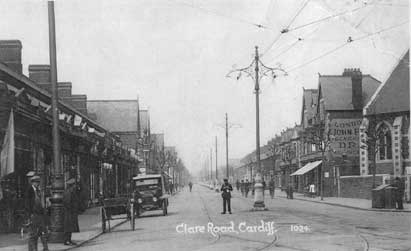

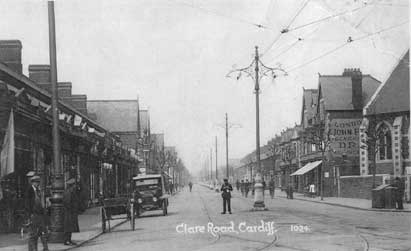

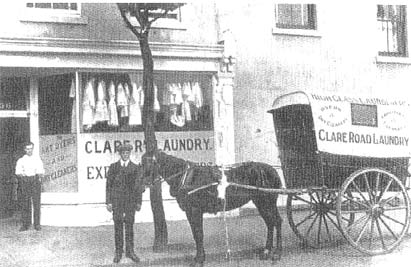

Clare Road, from Penarth Road and then (below),

Penarth Road near the Clare Road junction. The old Penarth Road methodist church

on the corner has been replaced by a supermarket after first closing and then

being badly damaged by fire in the 1970s.

More photos of Grangetown then and now

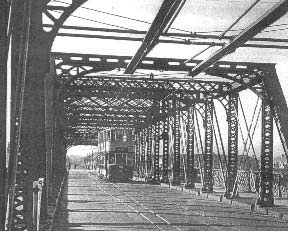

| JULY 25-26 1886: A bridge too far

Two nights of disturbances in Grangetown made the

national news, as workers held a mass demonstration against tolls being introduced on the road linking the suburb with their workplaces in the docks.

It centered on a swing bridge at the Old Sea Lock over the Taff in Penarth

Road, linking Grangetown with the docks. It was a private road leased

by the Taff Vale Railway Co and which had cost £60,000 to build

in 1861.

Suddenly the company wanted to enforce its rights. Working men were

to be charged a penny for walking over the bridge, and the toll rose for

those with animals or in carriages. The Western Mail reported that

almost every resident of Lower Grangetown was against the toll, which

would lead to hardship and inconvenience in many cases. By the first day,

around 100 householders had already decided to give notice to move, because

they could no longer afford to live in the area - and the paper mooted

that if this continued, the area would soon become "a deserted village".

By 5.15pm on the toll's first day, feelings were running high and crowds

of men, women and children headed towards the toll-gate, as workmen started

heading for home from the Docks. When workers returned

again that evening, a crowd of about 1,000 gathered again and a group

of ship's carpenters took the gate off its hinges and threw it into the

river.The Times reported that 1,000

men took part in the protests each day against the railway company. There

had been "upmost good humour" for the most part, as 200 police stood by,

but then there was direct action. "They rushed at the newly-erected toll

gate and tore it from its hinges, throwing the structure in the river."

The first gate was replaced the following

day, as well as a sentry box for the toll-keeper. The toll house

was also damaged. The paper later publishes court reports

of three men who were arrested for causing the damage, costing £5

- Cornelius Dacey, William Smith and William Webb, all under 23. Police

were also after another man called William Drew, who was heard to shout

"Go it boys, that's right, pull it off!" The court was told of "200

armed navvies with iron bars up their sleeves." The three were found

guilty and the judge expressed sorrrow at having to sentence them to a

month's hard labour.

There were attempts to resolve the issue, before and after the direct

action. The matter was raised at a public meeting on July 20th at Clive

Hall, chaired by Mr Alderman Jones, in which it was agreed to send a deputation

to the company. But the bureaucracy and resistance by the company prevailed.

By the time the toll was brought in the following week, some of the 600

men who daily used the bridge decided to take the long route via Penarth

Road and Bute Street or catch a tram, rather than pay the toll. They even

tried to start a ferry service, costing a halfpenny. After the mini-riot,

negotiations continued between borough and company, which eventually led

to a commuting of the toll for foot passengers, as the company were unwilling

to sell the bridge and road to the corporation. Problems continued and

the head at St Patrick's School noted in August a fall in pupil numbers

- "many families are leaving the neighbourhood owing to the enforcement

of the toll in Lower Grange." The same in November, with the situation

having "made a great difference to the attendance of the school, many

families having removed in consequence."

But the men won an eventual victory. It led to the corporation building

the Clarence Road and James Street swing bridges, and the railway company's

bridge was dismantled within 10 years.

|

1895: Grange Gardens

Grange Gardens was a gift to Cardiff in

1894 by Lords Bute and Windsor, who owned the land on which it stands. Just

over 9,000 square yards belonged to Bute and 5,764 square yards came from the

Windsor estate. The bandstand cost £2,374 and was constructed at the same

time as one in Victoria Park. However, it was complicated by the fact the wrong

foundations were laid for the bandstand in Grangetown. "Grangetown Gardens"

were opened on June 19th 1895 by councillor Joseph Ramsdale, the chairman of

the parks committee. "A very large number of the inhabitants of Grangetown"

gathered for the ceremony and the mayor proposed a toast to Lord Bute and Lord

Windsor. Mr D A Burn's Roath brass band entertained with a selection of tunes.

There was also a celebratory dinner later.

Above is an Edwardian photo of Grange Gardens with the original bandstand.

See the little boy tying his shoelaces before joining his friends in the background.

The war memorial was added in 1921 at a cost of £1,000. Was this lad in

the photo one of the ones who returned safely? Interestingly, a plaque was added

in 2000 in memory of Private W Langstone, whose body was only found nine years

after the end of the war and who was missing from the memorial. Surviving members

of his family attended the ceremony, along with representatives of many service

organisations. A further plaque to later Grangetown war dead has been added.

You can read more about Grange Gardens' history here and there is a lot more about the Grangetown War Memorial and the men on it on our

World War One project website

| 1891-1901: Saltmead grows up,

a little forgotten

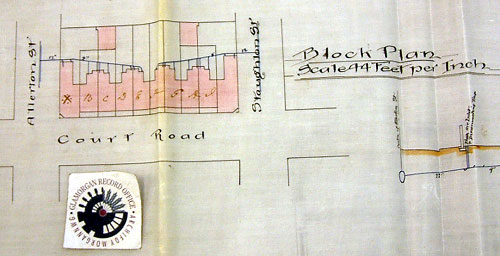

This block of cottages in Court Road,

along with a grocers and butchers's shop on either corner, were built

in 1891-92 by builder David Davies.

The homes and shops opposite were built by WT Ellery four years before.

You have to look hard these days to

find evidence that Saltmead as a place, ever existed. Which is a shame,

as a case has been made for an area which developed semi-independently from

Grangetown. The salt marsh "Saltmede" is mentioned in the Valor Ecclesiasticus

(1535). Saltmead Presbyterian Chapel was built in 1901, on the corner of Hereford

Street and Avoca Place - there is now a modern replacement building. We

still have a Saltmead surgery in Clare Road. But the name seems to have

dropped out of use and fashion. Local historian Colin Weston made the argument

in his short history of Saltmead, which appeared in Grange News in

1981. For him, Saltmead was a "forgotten district of Cardiff". It became

known as Upper Grangetown sometime in the 1930s, as Saltmead was swallowed

up.

"Unlike Tiger Bay, Saltmead was a real place, yet in many ways it

was very similar to the Bay. Many different races settled in Saltmead,

men gambled on street corners, police walked around the area in pairs.

Here and there some households had donkeys in their back kitchens and

pigs in the passage. The roads were very empty in the early days, except

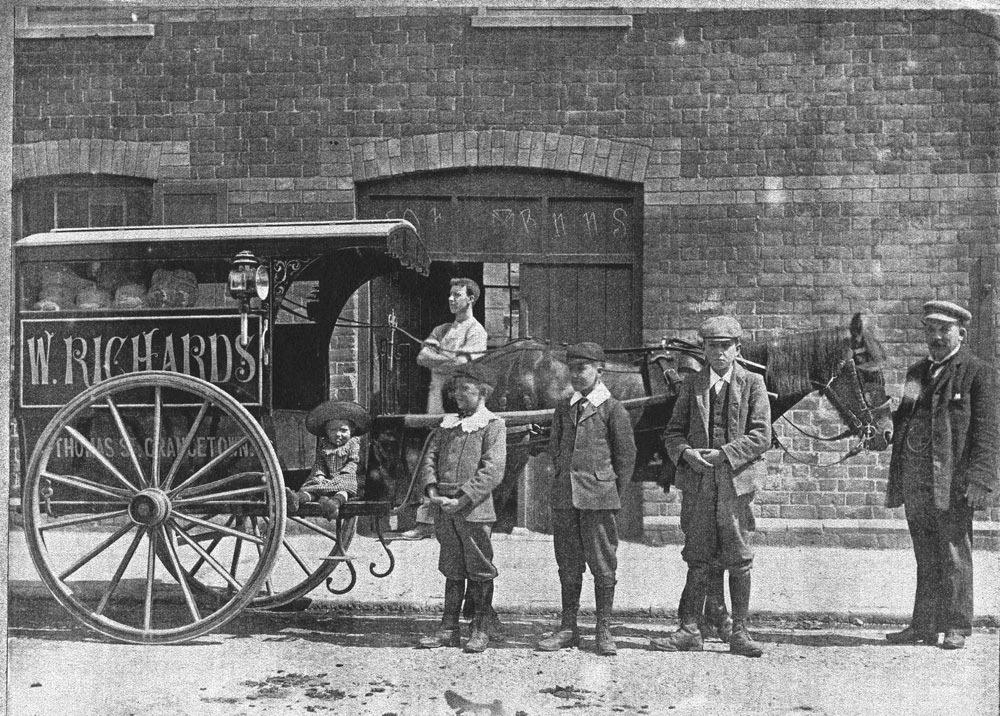

for the horse and carts of the milkman, coalman and the local builders."

Saltmead is quite evocatively described in a memories column from an

old Cardiff newspaper in 1940, looking back to when the houses were built

on former farmland behind Clare Road for £120 each - a bigger yield from

the rents of the growing migrant workforce than brought off farming the

land. Rents were charged of six shillings a week - nearly a third of the

working man's not always regular income. It admits that they could suffer

wage loss due to rain or frost and looked elsewhere.

"Old Salt" writes: "In days gone by, owing to the influx of new workers,

promised employment in the town and unable to find it, the practice arose

of these workers hawking coal with donkey carts. The cart was parked in

the roadway at night but the donkey was led through the passage and stabled

for the night in the kitchen."

It is not hard to imagine those builders' carts, when you look at how

Saltmead quickly developed from the end of the 1880s. It was not without

its problems - builders' strikes, short-term housing slump and problems

with drainage from building on marshy land.

In July 1890, Stephenson and Alexander

(agents still in existence today) held an auction at the Royal

Hotel. It included 70 lots of building land for development. These included

part of Allerton Street and what is now called Sussex Street (then Staughton

Street), and a large tract of land between Somerset Street, Compton Street

and Hereford Street, off Court Road, which was offered as either land

for industrial development or "small houses...which would easily secure

tenancy." The roads and sewers had already been put in place; all was

needed was the houses. There were also 35 houses offering rents totalling

£189 5s 7d. One house in Dorset Street, commanded a rent of £1 6s and

8d, while a bakehouse on the corner of Staughton Street and Court Road

was worth £6, 8s. However, an earlier sale in 1887 had attracted "meagre"

interest according to the Western Mail, and proceedings were called

to a halt after low prices for some building land in Court Road.

Court Road, as an example, with its late Victorian terraced homes is

a fascinating snapshot of this piecemeal development, as well as how people

moved to Cardiff.

The old Saltmead Presbyterian Chapel, a photo taken in about 1980 - the old

building is now gone, as you can see from the change photo, with a smaller

church next to a flats development.

The road started to be built in the 1880s. At first glance, it's just

another terraced street but you quickly notice the different styles to

the houses along it, reflecting the numbers of builders involved and the

time it took to complete. You can still see the date 1887 over the doorway

of Number 8 and this end of the road was mostly developed from this time,

but it was slow progress. Building continued off and on over the next

eight years. Houses had sculleries and kitchens, and the plans show outside

toilets and coalhouses. Some of the corner shops had stables for up to

four horses and coach-houses. Typically of the area, a number of different

builders were involved: Llewellyn Thomas built more than a dozen homes

and shops in Court Road between 1887-88, but others like W T Ellery, David

Davies, Alfred Dando and Llewellyn Preece built smaller numbers. The Court

Road School also stood where the newer homes off Rutland Street and Courtmead

Gardens stand today, opening in 1893.

In 1893, there was a bit of a "stink" over refuse being buried in Grangetown's

open spaces, which were the new building sites. There was a difference

of opinion between Cardiff's public health official and surveyor. The

former believed it was "very undesirable" to make use of "offensive refuse"

from elsewhere in the town, but the latter argued "a man might as well

object to the use of manure in his garden." He believed that a similar

burial of "carefully selected" waste at Ely Common had not been a health

hazard. There was nothing wrong with vegetable matter, offal and filth

finding its way under the new houses. But it certainly aroused enough

controversy to need a public meeting. The "Man About Town" column in the

Echo poured scorn on the "pathetic touch" of "indignation of the

good people of Grangetown having their new homes built on refuse."

Interestingly, by the early 1890s, local councillor SA Brain had been

complaining about the "swamp" in Saltmead, so much so, that

he believed he was regarded as a nuisance at the authority. These problems

with the new housing by 1898 became known as"Saltmead swamp" scandal.

Cardiff's medical officer found drainage and health problems due to some

homes being built on clay, with stagnant water under the floors. Dry rot

had affected the woodwork, with damp in the walls. The Western Mail

criticised the situation, questioning the planning process and builders,

saying the "poor were being choked out of existence in the Saltmead swamp."

"The fool who built his house upon the sand was a wise man by comparison

with the builders of certain streets in Saltmead." Homes were slowly

rotting away, "built on filth" - on pools of stagnant water and ditches.

A cattle market would be cleaner, "and a prison brighter, healthier

and purer", said the Mail. The reporter found 30 empty houses,

boarded up in Stoughton Street, some tenants moving upstairs to live.

There were another 14 empty houses in Hereford Street, 16 in Saltmead

and Court roads and six in Allerton Street. One town engineer had tried

to blame the rough neighbourhood and tenants "knocking about" their homes.

But the reporter could see why some would have looked for distractions

in the pub and elsewhere due to the "noxiousness" of the place they call

'home.'

The borough inspectors visited houses in Compton Street, Somerset Street

and Saltmead Road. As well as finding a list of building and drainage

defects, they saw tenants with symptoms of rheumatism. But they also found

that not all homes were affected and there was evidence of maltreatment

of houses by "careless and indifferent" tenants. Councillors

visiting the area found workmen on roofs and in backyards in Court Road

and Compton Street, where bricks were simply crumbling away in some houses.

One resident complained of rats and how his wife could not keep their

children's feet dry indoors in wet weather:

"At one house in Compton Street there was a hole in the passage

near the door, and the occupier informed his visitors that every night

the rats from the space beneath crawled up and held high revel in the

rooms. The water came into the house from the street on account of the

defective shutes, and it was impossible for his wife to keep the children's

feet dry indoors in wet weather. "

Feet sank in the backyard

at another home in the street "several inches into the sodden, ill-smelling

soil." A floorboard was taken up underneath a house in Court Road

and 3ft beneath was a mass of foul-smelling slush. The issue was enough

to create concerns for the housing planned for the roads laid out between

the Taff and Clare Road - now Taff Mead, which had been used to bury refuse

and where children used to swim and skate on ponds.

The censuses of 1891 and 1901 are wonderful tools for giving a snapshot

of what Grangetown was like more than a century ago. The area today is

profoundly multi-cultural, not just with Asian and African communities,

but with eastern European migrants and a population which changes by around

a fifth every five years. At the end of the 19th century, the growth of

Cardiff as a city was driven not just by the general population rise,

but by the migrant workers who moved from rural parts of Wales and England,

other towns and cities and Ireland. Saltmead, provided housing for a time

when the town's population grew rapidly. The 1891 census shows Court Road

partly developed with around 50 homes - many of those living there are

workers who had moved from Somerset, Gloucester, Bristol and other rural

areas. The Clare Road-side of the terrace seems to include a number of

railway workers, but there are trades ranging from blacksmith, butcher,

groom to tailor and sawyer. A few homes also took in lodgers and boarders.

William Causey, a Devon-born carpenter lived with his wife and four children,

all under four - but also took in two boarders from his home town, who

were plumbers!

By 1901, the pattern of workers settling in the boom town continues,

although by now the whole road has been constructed. Into one of the last

block of homes to be built were Devon-born James Youlden, 48, who was

a boildermaker's helper (later ship rivetter). He lived with his wife

Elizabeth, 42, born in Gloucestershire, and their three sons, aged 13

to 16, all born in Cardiff. The family had moved from nearby Devon Street,

where the two youngest were born. The eldest Robert worked as a waiter

in the railway rooms. Another Sam later became an engine driver, according

to local records, then an electrician/labourer, while son Charles became

a teacher and the family moved to Severn Road in Canton. Next door one

side lived Charles Davies, 51, a stonemason, and wife Mary, 56, both originally

from Ross-on-Wye. Their four children included the eldest, Mary, 21, a

"domestic" and son John a butcher's assistant. The other side of the Youldens

was tailor Richard Giles and his wife Emily, both 38, orginally from Monmouth

and their two children. Other neighbours of the Davies family were John

Reed, 40, who was a more recent migrants. He was born in Hong Kong, while

his wife Annie, 40, was a Londoner. They had brought their eldest daughter

from London, but youngest Olive, six, was born in Cardiff. Living next-door

to them is water clerk Godwin Palmer, 33, wife Cicily, 29 and three young

children. They were another couple from Monmouth.

Court Road has only one shop today, but at the end of the 19th century

- before cars - it was a busy mix of shops and terraced homes. In 1899,

according to the Western Mail's Cardiff directory of the time we

find five grocers, three butchers, two green grocers, a newsagent, other

unnamed shops. Edward Ribton's fried fish shop is now a mid-terrace house

a block away from the surviving corner shop.

By 1890, the first few homes had been built on Cornwall Street, Court

Road, Allerton Street and Hereford Street, but other streets would follow

within a few years. Given the origins of so many of the population, it's

not a surprise then that street names like Cornwall, Hereford, Somerset,

Monmouth and Devon appeared in this part of upper Grangetown. Other names

were eventually changed - Staughton Street became Jubilee Street and Sussex

Street, Saltmead Road became Stafford Road.

Some of the street names in other parts of Grangetown owe their connections

with the Plymouth estate. As well as St Fagans and Rhydlafar streets,

there is also Penhevad, Pentrebane, while Stockland Street is named after

a farm north of St Fagans upon where Royalist and Cromwellian troops fought

a little-mentioned bloody battle in the Civil War.

Spaniard's adventures in Saltmead - from Cardiff Times, 1906

"The salubrious neighbourhood of Saltmead still appears to contain pitfalls for unwary seamen. Spanish fireman Francisco Garcia arrived in Cardiff and met Gertrude Brown, 29, and Emily Duffy, 27, whilst walking the streets at four o' clock in the morning. He was invited to a house in Stoughton Street where he saw a third female, Anne McDonald, 45. Duffy took charge of him and he went to sleep but on waking an hour later discovered his purse, containing £2 6s was missing and Duffy was in the act of pulling at his watch chain."

|

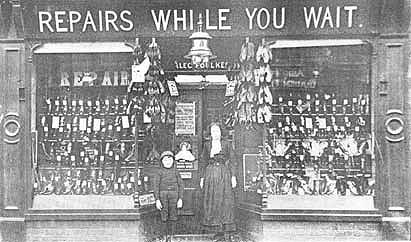

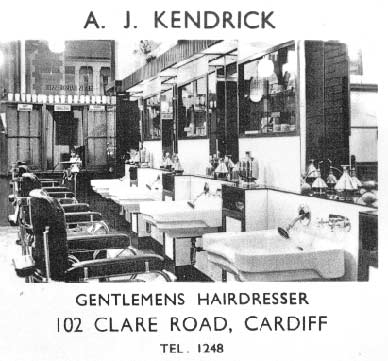

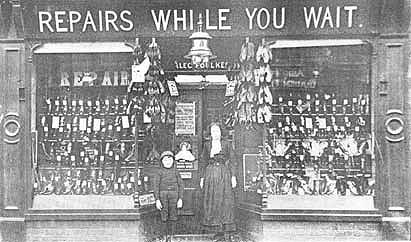

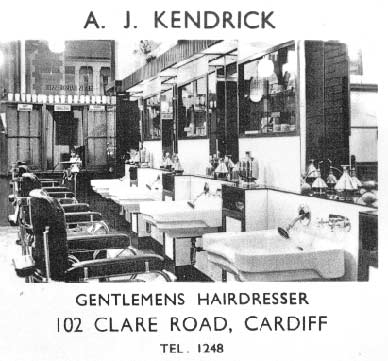

Foulkes' shoe shop in Holmesdale Street in

1914. Nowadays you can only get sole - it's the Holmesdale Street Fish Bar!

Before that in the 1880s, sign-writer Edwin Johns lived there. Pictured right

is an advert for the barber's in Clare Road - now a private house.

| APRIL-MAY 1893:

"That business, pure and simple, appeared to be consuming as much beer

as they possibly could"

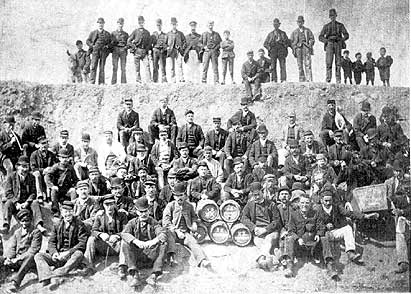

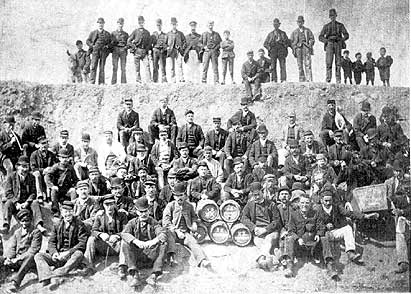

The Hotel de Marl, as photographed by GH Lawrence of Cardiff.

It was seen as remarkable at the

time, and it looks pretty odd even today - but hundreds of Grangetown men

got around the Sunday drinking laws in 1893 by founding open-air "gentlemen's

clubs"

The practice had been going on for several months when it became the

subject of a court case in April 1893 - and the landmark ruling gave rise

to a brief but infamous flurry of more open-air drinking in Grangetown.

The first recorded example was in a field in what is now known as Sevenoaks

Park. It lay between Penarth Road and modern day Sloper Road, known as

Tanyard Road (after the Tannery) back then.

Police had already been monitoring the Sunday morning exploits of a group

of local working men, who would dig a hole in the ground to be used to

gather a kitty of 4.5 shillings. And then they would bring a 4.5 gallon

cask onto the field. Eventually it to led to a court case, where James

Donovan was accused of breaking the Sunday licensing laws on 2nd April

1893. Giving evidence, two policemen, from the vantage point of the signal

box on the railway embankment above, said they had noticed a group of

up to 16 men gathering by 10am. This group grew to 38 by 11.30am, according

to one of the officers. A cask of beer, bought from Mr Gillard's shop

(Holmesdale Street), was placed by a John Parle - a mason's labourer from

Thomas Street - on a fence and beer drawn into a tin can and glass. The

officers claimed a man went around the group, seemingly to gather money

- illegal according to the laws.

Now at this time, behind closed doors, gentlemen's private clubs could

serve - if not sell - alcohol on a Sunday. This grey area was where

the legal argument was heard in court, with the stipendiary magistrate

taking two days to reach his decision. Could a field be defined as a "place"

to consume alcohol under the Act? While there was also doubt whether men

chipping in to buy ale was the same as someone selling alcohol.

The stipendiary magistrate ruled that the gathering of humble working

men constituted a club. It was "a rude and elementary type but still a

club", as much as "the best and most exclusive in the country."

He ruled in Donovan's favour.

With this legal obtacle removed, the practice soon drew bigger crowds,

spread elsewhere in the area and gained national notoriety. Pits were

dug 8ft deep in the clay ground of The Marl across Grangetown to form

the walls, carpet was laid out and up to 400 men sat around, as beer was

poured freely from casks from 7am until 9pm at night. No alcohol could

be officially sold, but members made "donations," with sixpences

and pennies collected in old copies of the South Wales Echo. By

all accounts, this arrangement was fairly observed and the men were impeccably

behaved. As one of the organisers said, likening the activity to the champagne

drunk in the private members County Club in Westgate Street: "Them pays

as likes and we all drink square."

The Echo's correspondent joined the group for refreshment at the

"Hotel de Marl" on May 7. The reporter found 70 men, seated

in a cresent shape in two rows, with the chairman of the gathering, known

as "Jeremy." The report says: "He occupied an elevated position

on a 4.5 gallon cask of double X beer (empty)...a man called 'Bill', humourous,

red-whiskered and as it transpired, strictly law-abiding character, acted

as drawer". He filled the men's decanters while they, from time to time,

put money into a "tattered" copy of Saturday's Echo. Fresh supplies

were brought from a licenced drink wholesalers in nearby Clive Street.

It was estimated a 4.5 gallon cask was consumed every 20 minutes. The

reporter, on the edge of the pit, was "good humourly" invited down and

offered a glass of beer. "One glass of that beer was enough for anyone

who really valued a good draught of the national breweries."

"The civility of the crowd was no less remarkable than their determination

to obey, while this consented to be the law and to avoid creating a nuisance

and a scandal," said the correspondent. He said there were "no loafers

or corner boys," juveniles were ordered away and the majority of the crowd

were "working class masons, fitters, engineers, a few dockers and sailors."

He added: "If questioned, I should positively deny that the men I saw

were idlers, or blackguards or scoundrels of sorts."

The reporter also saw some "well-dressed people," possibly on their way

back from church or chapel. Another account reported a group from a theatrical

company, who were playing in town.

"They were working men, pure and simple, with a flavour of strong language

and stronger tobacco but undeniably wage earners," said the Echo

man.

A separate account in the London Pall Mall Budget found people

turning up in cabs "laden with kilderkins of beer" from as early

as 7am. Fourteen kilderkins (about seven barrels) had been drunk

in 10 minutes. Quoting The Morning paper in Cardiff, it was estimated

there were 360 "club members" and another 1,500 spectators. "It appears

almost incredible that the proceedings should have been so harmoniously

conducted as was the case," reports the paper. It found "perfect order"

as the various clubs were "engrossed" in emptying 4.5 gallon casks

and to remind one another there was not sufficient money on the carpet

to pay for the next, "to pay much attention to anything but the business

in hand."

It added: "That business, pure and simple, appeared to be the consuming

as much beer as they possibly could."

Up to 5pm, more than 80 4.5 gallon casks were emptied, but after retiring

for tea, a "roaring trade" was expected in the evening.

After the attention given to the field club, the "disgraceful exhibitions"

were attacked by Canon Thompson in a lecture to the YMCA. He appealed

for an end to the "club", for the influence it might have on

children. By June, Lord Windsor had banned drinking on his property and

threatened arrests for trespass for anyone found drinking on the Marl.

The drinking club was also taken to meeting in other locations near Canton

Common, as well as meeting at the Marl just after midnight to avoid police.

Another club was reported in a field off Clare Road. The Western Mail

remarked that while Sunday was usually the quietest day of the week, in

Grangetown "it was just the reverse." The scenes taking place were "disgraceful

and demoralising."

* There had been an issue for a few years regarding the 1881 Sunday

drinking laws in Cardiff. There were claims of hundreds of "shebeens"

- illegal drinking dens - in the town. Newspapers speculated that the

large Irish community was one factor for their popularity. In 1889, a

Royal Commission heard evidence that there were 450 shebeens in the town

and that police raids couldn't contain the trade. The Western Mail

sent a team of ordinary people under cover to investigate their extent.

In Grangetown, they found 40 shebeens with 173 people present - Cardiff-wide

it amounted to 3,196 in 457 shebeens. There were around 58 people in one

alone in Andrew Terrace, five shebeens in in Hewell Street and Havelock

Street, four in Lucknow Street, two each in Saltmead off Cornwall Street,

Cornwall Road, Court Road, Hereford Street, Holmesdale Street and Sevenoaks

Street, other shebeens in Andrew Terrace, Bishop Street, Courtenay Street,

Earl Street, Newport Street, North Street, Oakley Street, Plymouth Street

and Redlaver Street. Dr Gibbins, the curate at St Paul's Church in Grangetown

said the Sunday closing act had had an "evil effect" on the

area, with drinking been driven underground in clubs and where illicit

drinking in homes had become "widespread." The inspectors also

found illegal drinking in shops, including two fried fish shops and a

barbers. Convictions were running at one a day in 1891-92. In February

1892, police raids included houses in Earl Street and Cornwall Street,

with 4.5 gallon casks of beer confiscated. In October, police found 17

people drinking at William Jones' house in Dorset Street - 11 of them

women. Charles Morgan in Saltmead Road said he had to provide for his

family, as he had been in hospital.

A court report from 1898 is typical: George Bennet, alias Harry West,

was summonsed for selling beer without a licence at a house in Compton Street, after a police constable had watched on a Sunday morning in April:

"He saw six women and four men enter, and five men and two women leave.

A man, named Thomas Hackett, carried into the house something like a 44-gallon

concealed under a sack. In the passage he met a woman, named Kate Leeley,

with two pint bottles underneath her cape, aud in the back kitchen he

surprised two women and a man. who were refreshing themselves with beer."

|

|

1899-1912: Distress and disease

Of all districts in Cardiff, Grangetown

had the highest number of people classed as paupers, who were granted poor

relief by the Cardiff Union. There were two types - those, mostly men, who

were in the workhouse (the old St David's hospital site in Cowbridge Road)

and the others, mostly women, who lived in the community as "outdoor

paupers" but were granted a few shillings a week to live on, or payment

in kind in the form of food, boots or medical expenses. Their experiences,

as listed in the Cardiff poor relief books, show a myriad number of maladies

and misfortune. There is simple old age, widowhood and infirmity, people

who have lost limbs or are blind, others succumb to phthisis (better known

as tuberculosis), bronchitis or are senile. Others have been "deserted"

or their husbands are "at sea" or "in prison". Others

are simply classed as destitute.

Few streets in Grangetown escape unscathed. At the end of the century,

Grangetown has a list of 195 families receiving "outdoor" relief. Across

the town there were a total of 140,000 days relief paid out, with nearly

24,000 in Grangetown. This list of families steadily rises past the 300

mark by 1906 to a peak of 330 in 1911 - a total of 838 adults and children

out of 13,291 in the town.

In 1906, for example, across Cardiff, there were 11,798 people receiving

"outdoor" relief, with 709 of them (at its highest 311 families) in Grangetown,

broken down as 91 men, 273 women and 345 children. Admittedly, Adamsdown

and Splott at this time were counted as separate districts, which if combined

would have seen 964 people classed as paupers in the community. In addition,

1,342 men, 729 women and 683 children in Cardiff were receiving workhouse

relief, with another 4,425 people classed as vagrants.

* If you want to view the poor books for yourself, the volumes are kept

in the local studies section of Cardiff Central Library.

Infant mortality was an issue of real concern at the end of the 19th,

start of the 20th century. There had been improvements in sanitary conditions,

the start of vaccination but the numbers of children, dying of malnourishment

for instance, had actually gone up in urban areas at the turn of the century.

To compare, today in Wales the average infant mortality is five deaths

per 1,000 births - in 1902 in major towns it was 146 deaths per 1,000.

That was around 150,000 babies dying a year. It was worse in the large

northern towns and cities, especially where women went out to work - they

could be back in factories and mills a month after giving birth. In Cardiff,

health officials prided themselves that the death rate was the lowest

of all towns of a similar size, and half that of places like Liverpool

and Manchester. If you look at Grangetown, it did show up as a pocket

for deaths in diseases like diphtheria, compared to other parts of the

town. Diarrhoea was also a killer - especially in hot summer months -

in the days before fridges - cases rose 70% in the first few years of

the new century. In 1900, in one three month period in Cardiff there were 611 deaths - of these, 212 were babies under one and 276 were children aged between 18 months and five years - only 81 were deaths of people over 65. (Broken down there were 62 diarrhoea deaths and 21 from diphtheria; other causes were whooping cough, scarlet fever and typhoid) Grangetown's death rate was 15.9 per 1,000 compared to a Cardiff average of 12.5.

There were studies, inevitably, into the causes. Some dismissed arguments

over poverty, claiming bread and meat were cheaper and wages were higher.

Some of the health arguments are familiar to us today - issues like breast

feeding, while there was criticism of diet and the basic milk substitute

products of the day. The conclusions, which did lead to improvements within

a few years, were that women needed more health and nutritional care while

they were pregnant - and again after they had given birth. In Cardiff,

they had a public meeting in 1905 to address the issue of underfed children

in the town's schools - so there were issues of nutrition for some children

who were older.

|

| JANUARY 12 1895:

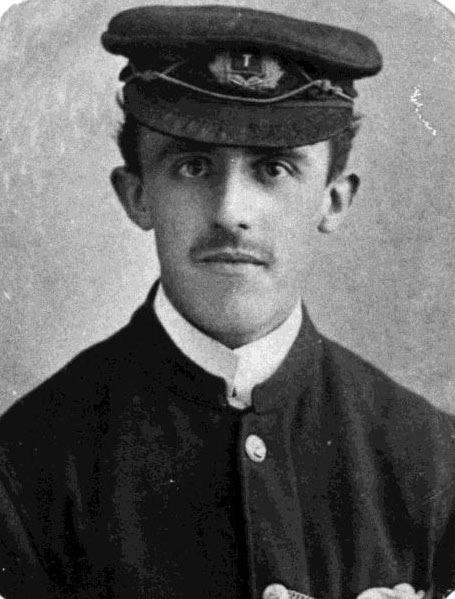

Ice tragedy for local rugby star

This particular sad story illustrates

something of what it was like in what is now the Taff Mead area, before

Merches Gardens, Hafod and Mardy Streets were built at the end of the century.

As well as being an area for dumping some of the town's refuse, there were

also brick ponds between the River Taff and Clare Road. These ponds seemed

quite large, and were popular with townspeople for recreation. They were

on privately owned land, leased by a Mrs Jones of Francis Street (now Franklen

Street) who would charge a 3d toll for entry.

In winter, when they froze over,

the ponds were popular with skaters. On this particular Saturday, tragedy

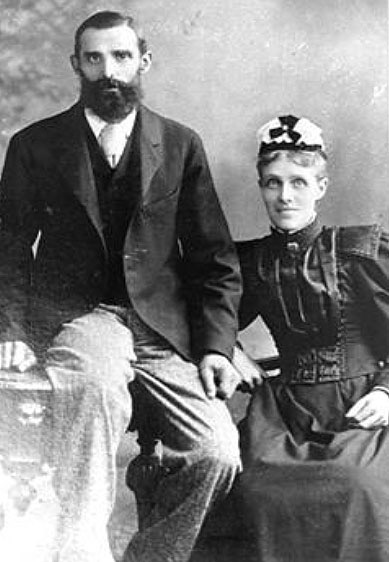

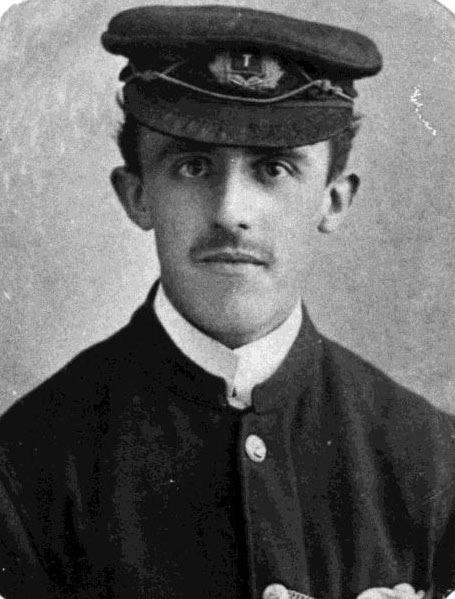

struck involving a well-known local rugby player. "Dick" Davies (left)

was 26 and was a "dashing forward" for Cardiff football club. On this

particular weekend, he couldn't join his twin brother William and the

rest of the squad because of an ear injury. They had travelled all the

way north for a match at South Shields. Dick instead, visiting his mother

and sister in Allerton Street, joined up to 300 other people skating.

He was one of half a dozen men who went through thin ice, as it grew dark,

10ft from the bank and left struggling in 12ft deep water. Poles from

a building shelter were thrown across the pond for the men to reach. Spectators

used planks and linked hands to try to reach them. In winter, when they froze over,

the ponds were popular with skaters. On this particular Saturday, tragedy

struck involving a well-known local rugby player. "Dick" Davies (left)

was 26 and was a "dashing forward" for Cardiff football club. On this

particular weekend, he couldn't join his twin brother William and the

rest of the squad because of an ear injury. They had travelled all the

way north for a match at South Shields. Dick instead, visiting his mother

and sister in Allerton Street, joined up to 300 other people skating.

He was one of half a dozen men who went through thin ice, as it grew dark,

10ft from the bank and left struggling in 12ft deep water. Poles from

a building shelter were thrown across the pond for the men to reach. Spectators

used planks and linked hands to try to reach them.

The Western Mail reports how Dick "struggled manfully" and was

seen trying to remove his coat - which onlookers say may have entangled

him. But he was too far away and disappeared before assistance could reach

him. Peter Lynch (101 Clare Road) recovered his body half an hour later

and it was taken to the mortuary to be identified by his mother and sister.

Two other lives were saved by a Norwegian sailor, George Jacobsen. E J

Humphreys, from Adamsdown was rescued after grabbing hold of a plank.

"They laid me on the bank and started pumping me, they thought I was passed

recovery," recalled Mr Humphreys, a non-swimmer. He was taken to the Neville

Hotel, where he was given clothing and refreshments by the landlord Mr

Gillard.

Dick was employed by the Barry Railway Company as a plumber and he lived

with his brother-in-law Frank, an engine driver, in Barry. Dick had briefly

left Cardiff to work in Huddersfield during a builders' strike and was

selected for the town's team. "A genial young fellow, liked by everyone"

he was due to be married in the summer to Prudence Goodhall. His body

was taken to his mother's house at 19 Allerton Street. She had been making

his tea when he drowned and cried repeatedly "if only he had gone to Shields"

when she heard the news. The sad news was telegraphed to Tyneside and

Charlie Arthur, Cardiff rugby club's secretary, who relayed the news to

Dick's brother and the team. A F Hill, captain of Cardiff, led the funeral

procession on the Wednesday from Allerton Street, swelled by members of

other local rugby and cycling clubs. The pall-bearers were four members

of the Cardiff team. A special train had carried 250 of his work colleagues

from Barry. He was buried in his club colours.

* An earlier newspaper report from

1893, comparing skating ponds across Cardiff, called another 3ft deep

pond off Ferry Road at the Grangetown Brick Works, "the finest piece of

ice in the town." A small charge covered the hire of skates and you could

have a coffee from a cottage next to the pond. There was

also a Dumballs pond, off Penarth Road, "frequented by people whose

company was anything but congenial."

|

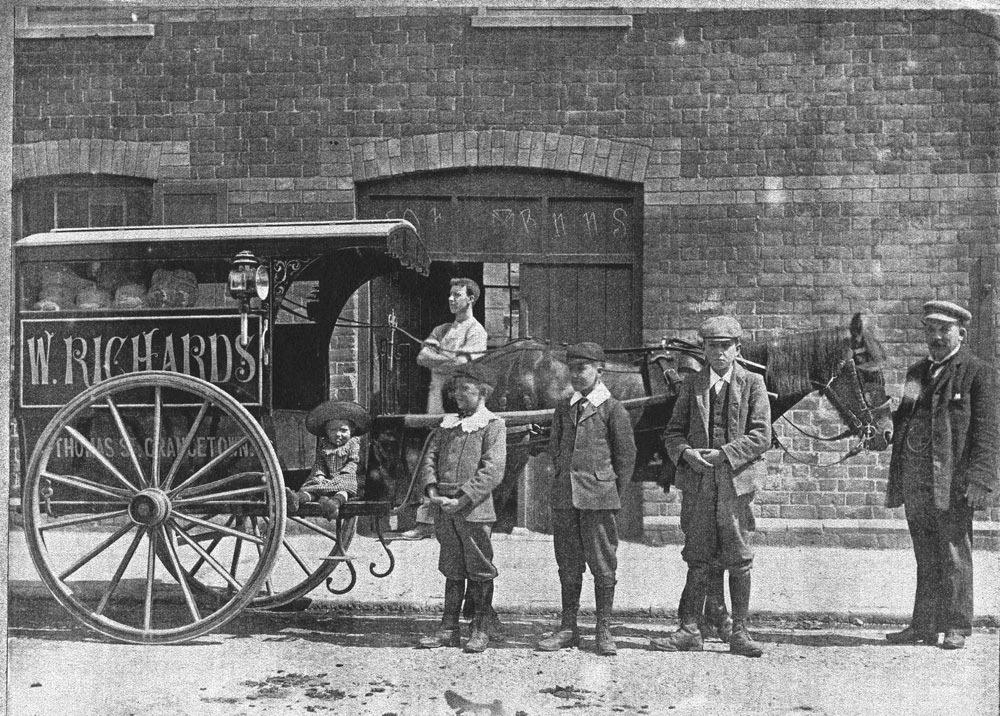

Here's a photo dated from about the turn of

the century, in Lower Grangetown. It shows Margaret Saddler standing outside her

son Fred's shaving saloon - near the junction of Worcester Street and Oakley Street.

She would have been in her early 50s at the time this was taken, her son Fred

around 20. Father Edwin was a sailor. These are two of the "disappearing"

terraces, which were replaced by modern housing and an OAP complex. The shop was

still a hairdresser's in the late 1920s.

Some of the earliest-built streets in Grangetown were demolished in slum clearances

of the mid to late 1960s. The first batch of streets to be looked at were Thomas

Street, Madras Street, Lucknow Street and some homes in Franklen

Street and North Clive Street in 1966. Many homes there had been

deemed unfit for habitation. Cardiff Council started compulsory purchasing the

streets. The values of the homes - which dated from the early 1870s - ranged

from as little as £85 to £1,400 depending on length of lease remaining

and condition. As the policy progressed, there were complaints about the state

of empty houses in 1967, with most people rehoused but a few waiting for new

flats near Lawrenny Avenue in Leckwith to be completed. The London Style Inn,

Penarth Dock pub and an old bakery were also demolished. The land was to be

used temporarily for a car and lorry park, and children's playground, before

the eventual building of the new St Patrick's School in Lucknow Street.

A second phase of slum clearance was also drawn up following health inspections

which identified 204 unfit homes in Knole Street, Sevenoaks Street, Oakley

Street and Hewell Street (above in 1937) - where its 70 homes

also made way for a new school and modern housing in the 1970s, after standing

for a century. The report found 226 families needed rehousing, with three pubs,

a surgery, dairy, betting shops, print works and 17 shops also affected. In

Grangetown Local History Society's Old Grangetown Memories Book One,

Alice Butler recalls: "We bought a house in Knole Street for only £120 because

there was not much lease on it, and when they knocked it down I had £1,000 for

it and moved here (Thomas Street)."

Reports to council found residents "anxious" to be rehoused back

in Grangetown as soon as possible after the slum clearance. In 1968, an action

area was drawn up for the Madras Street and Thomas Street area, which set aside

flats for 160 people - especially the elderly, with 45 homes in Thomas Street

built at a cost of £152,000 by Bond Brothers. The development also included

the new Catholic primary school, St Patrick's Hall, roads being closed off and

new paths linking Durham Street and Dorset Street.