PART THREE: Here is Grangetown history covering memories from the 1940s and 1950s onwards, including schooldays. Please email us with any stories, memories or photos. Return to Part One or Part Two

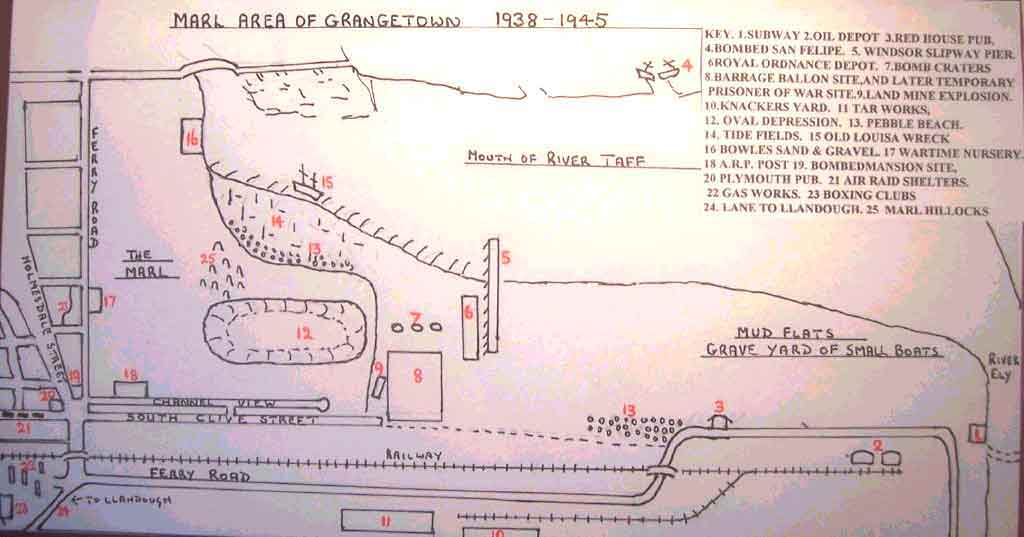

Nature alongside the Taff and Rhymney

By Jack Payne

When I was a young lad I used to collect

birds eggs, consequently I knew the countryside within and around Grangetown

like the back of my hand.

Sadly, most, if not all of this countryside as I knew it, has now disappeared.

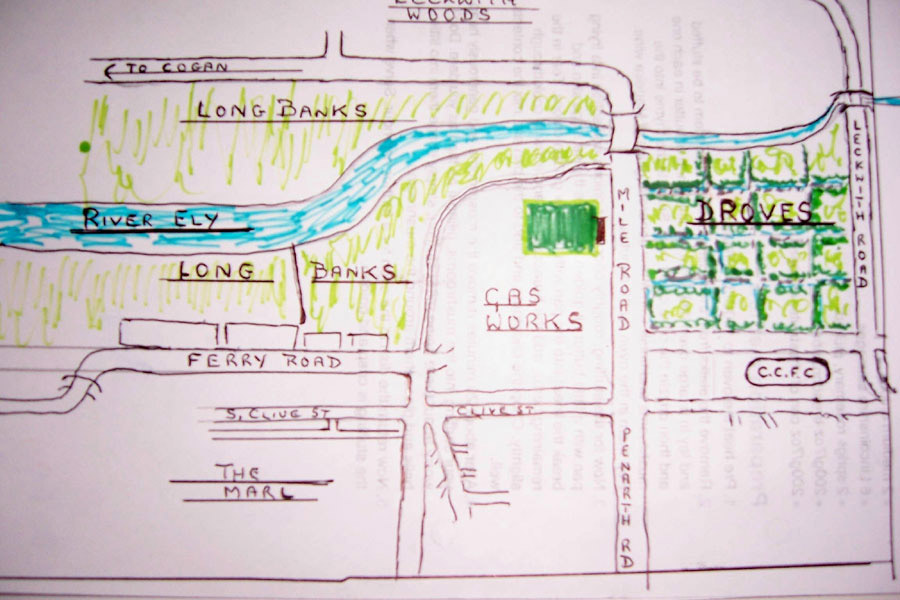

There was a large area to the left of the Mile Road bordering the River

Ely known as the Long Banks. This area of lush grass was once tide fields

but unlike those bordering the river Taff, which was criss-crossed with

gullies which filled when the tide came in. This area only had one gully

leading from the Tar and Oil Works in which nothing lived at the bottom

and the sides were caked with black oil.

The Long Banks themselves differed. The Lower Grangetown side had no easy

access because of the factories bordering Ferry Road. Access could only

be gained from the top end of the Gasworks Lane. Because of this inaccessibility

and the fact that the river no longer flooded this area, it was a haven

for wild birds breeding. Over time I collected snipe, lapwing, sandpiper,

dunlin, redshank, curlew and skylark eggs in this area. The opposite side

of the Long Banks had cattle and sheep grazing all year round, so consequently

with the exception of the skylark it was not a nesting site.

The other area of importance to wildlife was The Droves located between

the Mile Road and Leckwith Road.The Droves consisted of numerous grass trackways

with ditches and hedges on both sides forming borders for small fields.

One must suppose that in medieval times by its name it was used for droving

horses and cattle. Wildlife of all kinds were in abundance: Rabbits, hares,

foxes, pheasant, partridges, moor hens, coot, wild duck and close to the

Cardiff football stadium (Ninian Park) was a marshy area with very large

flat stones under which could be found frogs, toads and small lizards. At

the Leckwith end was a permanent Romany Gypsy encampment, where you could

see them sitting around a fire making clothes pegs and flowers from wood

taken from the hedgerow.

1950s: School days - baby boomers, 'Basher' Beynon and the G stream

By Ken Payne

Another memory of the Nash is the open fireplaces in all the classrooms.There

was no such thing as central heating. A coal fire behind the teacher was it.

In the winter time the bottled milk would be placed around the fireplace to

warm. When it was time for your milk break the teacher would ask questions,and

the first person with right answer would get the chioice of the warmest milk.

Again looking back it amazes me that no one got scalded or injured in these

everyday events.

Every week there was one afternoon dedicated to sport.The class would be put

in pairs in the playground, the most trustworthy at the front and the rear ,the

not so reliable near the middle of a line formed by the pairs. We were always

instructed to hold your partners hand as we walked. We would then go out the

school gates and walk down Clive Street to the junction with Holmesdale Street

and Ferry road.we would be seen across the road by the teacher,and then on to

the Marl playing fields. Here we were separated into group - boys and girls,

athletic types and not so athletic.The athletic boys would be organised into

football or baseball teams,or even into running events.The girls would also

play baseball or be given other exercises to do. The remainder,not so athletic,

would be made to walk circuits around the perimeter of the park until it was

home time.

At home time you were left to your own devices as how to get home, easy for

me as I lived right by the Marl. School in those days started at 9am,with a

playground break at approx 10.30am for 15 minutes, then dinner was from noon

till 2pm. Afternoon break was at 3.15 pm then the schoolday finished at 4.30pm.

I went home every day for dinner (no such thing as lunch) as did most

of my friends. It would be a quick meal and then out playing with my mates till

it was time to go back to school.There was no gymnasium at the Nash so the PE

classes would be in the playground (weather permitting). There was no such thing

as gym kit -you did your exercises in whatever you wore to school. Great fun

though. In the playground as we got older was where we learned to play “strong

horses". This involved three or four boys going up against the wall and making

a formation. The rest of the boys would then proceed to vault on to their backs,endeavouring

to land as hard as possible, until the formation collapsed in a heap of arms

and legs. The team holding the most boys being the winners.

Also there was whiplash: This

is where you formed a line, and all held hands. The biggest and strongest acted

as the centre point, he would start rotating round and round,the boys on the

outside of the line would eng up running full pelt until they let go or fell

over. I tried this in later life during football training exercises, and it was

really difficult to stay on your feet. The wall along the side of the playground

backed on to Clive Street police station, the holding cells right next to the

wall. I remember now expecting to see prisoners with arrows all over their clothes, a

general perception of criminals. The teachers seemed to be quite well known to

your parents and were given great respect. If they said or did something it must

be for your benefit, the teacher was always right. The school headmaster was

Mr Fred Parkin who was quite strict. I can recall "mitching" off school with

my brother to watch England play Wales on a Wednesday afternoon. We had just

got our first black and white television, and the game was on. However word got

round that we were watching the match, and six or seven other boys turned up

at our house to watch it. This was fine until school the following day, we all

had our excuses ready,however the first boy they asked why he was off school. "I

was round Kenny Payne's house watching the football" came the reply. Boy after

boy then relented and said they were at our house. The end result was six of

the best for me and my brother in front of the whole school. Painful memory.

I was now at the age to sit the dreaded 11 plus, which I passed. This meant a

change of schools though I really didn’t want it. Some of the boys who passed

decided to stay at the Nash, while others were drafted to various schools around

the area - Fitzalan, Canton High, Cardiff High for example.

I was selected to go to Ninian Park School on Sloper Road. Here the Council

had implemented a new system called the "G" stream. Because of the high number

of passes there wasn’t enough room for all at the High Schools, so this was

an additional class to take you through to O'Level. Looking back I think we

were used as a test to try the system. The boys that made up the “G” stream

came from several different areas. There were about 15 from Ely, 10 from Canton,

six from Riverside, the rest from Grangetown, making a class of 38.

I still recall the monotone reading of the register

every day: Appleby, Bolton, Bridges, Capel, Corsi and so on. This new school took

some getting used to for this class. For a start we were all strangers to each

other. Also we were the only class that had to wear uniform,a system that for

a while alienated us from the rest of the school. The rest of the boys in our

age group being put into three different class groups, A, B and C. The theory being

that the brighter members of the A class could graduate into the "G" stream, and

the other boys go up and down the classes depending on their ability. There was

in total upwards of 120 boys of the same age spread over these four classes. The

other thing I think about is the teaching. The same teachers taught all four

classes, so their range of pupils were in the extremes,not something you would

get at a conventional high school. At first we were the "posh" kids because

of the uniform, but eventually we were accepted as just pupils in the same school. Discipline

at this school was much tougher,some of the teachers had reputations to hold. Basher

Beynon, maths teacher, Moggie Slater P.E teacher, "Spud" Reynolds history teacher, were

a few that would give you the cane at the first excuse. However there were compensations, such as the

sports side of the school, which was excellent. Ninian Park prided itself with the accomplishments

of the soccer and baseball teams. The intermediate team was run by Mr Gough, the art

teacher,who had the uncanny knack of producing a team - a side that played as

a unit. I had the utmost respect for Mr Gough and my involvement with the football

team helped my integration into the school. Football games were played on Saturday

mornings in those days. We would have a team meeting Friday dinnertime to make

sure all the boys were available (I was never ill on a Friday), you were then

issued with your school football shirt. There was no such thing as substitutes

in those days,so it was ten outfield shirts and a goalkeepers jersey,and everyone

was expected to turn up,otherwise you played with what you had. Away games were

organised at these meetings,we would make our way to the central bus station

individually, here we would meet Mr Gough outside Asteys. Then it would be a bus

trip to Whichurch,Llanrumney or which ever district we were playing. We had to

provide our own bus fares,there was no school funding for this. After games we

would catch the bus back to the Central Station,and then make our own way home. One

of the benefits of playing for Ninian Park,was the occasional free pass to watch

Cardiff City on Saturday afternoons. We were a very successful side going through

the season winning all games,doing a league and cup double. We also managed to

win a "Tiger" football - this was the comic that introduced Roy of the Rovers to

the nations schoolboys. They had a monthly award for the most successful teams

at intermediate level, age 11 to 12, which the school team won. I thoroughly

enjoyed my football experiences in school, and still see some of the old players

around Cardiff. Classwork at the school was a different matter though. I struggled

with the change of teaching, the different classmates,and the homework. Whilst

at the Nash I hadn’t done any homework. This new intrusion on to time out of

school was difficult, especially as all my mates at the Nash wasn’t doing any. Also

at Ninian Park I was average at most things where at the Nash I was one of the

brighter pupils. This all made me struggle with the classwork. I wasn’t alone

with this as the majority of my new classmates seemed to be in the same boat. Obviously

some of the boys prospered and coped better than others but on the whole a lot

of us were not happy with our classwork. Disruption in the class was rife with

lots of misdemeanors and general bad behaviour. I’m sure looking back that the

root cause of all the problems was the size of the class. I’m convinced that

the class should have been split in two and therefore give each pupil more time

with the teacher. However I battled through school lessons and achieved some

level of success in exams, but not what I would have liked to achieve.

I think now that my own appraisal of those days is could and should have

done better. In general though I can look back and say I enjoyed the majority

of my days at school.

Being born in 1947, I was part of the baby

boom after the end of World War II. Having done a little research with friends

I can safely say that the average class size throughout my term in school was

approx 38 pupils. Starting off in Grange National (The Nash) as a five year

old, where you spent your early years in the infants. The head mistress was

Mrs Macarthur, I can also remember a Miss Lewis.Those early years seemed tc

consist mainly of play, sleep and story telling. Reading, spelling, times tables

and mental arithmetic were all to follow.One thing that strikes me now looking

back, is the order in the classroom,with in the region of 40 pupils in the class,the

order was immaculate with only one teacher. Consequently with that size class

some prospered and some fell behind. I can distinctly remember the class being

sorted so that the brighter pupils sat next to the slower learners. The object

was to encourage the slower learners to get help and encouragement off their

peers.I don’t know how successful the system was but it certainly was employed

as an aid to the teacher.

"The Nash" school was next door to Clive Street Police Station.

1950s: School days - spare the rod, spoil the child

By Graham Goode

Unlike the restrictions placed upon parents and teachers today the maintenance of discipline in the classrooms and sometimes in the homes seemed to be based upon the Biblical dictum: spare the rod and spoil the child. Mam could and did infrequently resort to using a wooden spoon to bring me to order if I was were overstepping her generally tolerant responses to boyish behaviour.

My Dad, on one occasion I remember, took me over his knee and strapped my backside with the belt he wore to keep up his trousers. This happened despite the protestations of my mother as, "He needs to be taught not to let good food go to waste." It was the custom on a Sunday for Dad to cook the Sunday dinner ('lunch' was for the posh). Proud of his organic gardening the wide range of vegetables were cooked and served. Inevitably I baulked at eating cabbage and on this occasion I declined to clear my plate. "Too many sweets before a meal," was the usual reason put forward by adults for children turning up their noses to good wholesome fare. But the continuing rationing of sweets and chocolate hardly allowed for confectionary bingeing. So the remains of the meal were served up at the next meal but I had refused to, 'clear my plate.' Exasperated, my father applied the belt with gusto and I found it more comfortable to stand awhile before being sent to bed without supper.

This was a rare occurrence for me although my brother testified to many more corrections of that kind and at a time when Dad had even more energy to lay on the strap.

I now eat cabbage without a murmur.

A slap across the backside or a clip across the ear was sometimes used to rein in any of my obstreperous behaviour. No hard feelings developed. The punishment was dished out and taken without harping on the degrees of justice or injustice that had occurred.

Generally I accepted it

as such. School was a different kettle of fish. My local school was originally

built as a Board of Education School maintained by the Council at the end of

the nineteenth century. It was inevitably referred to as 'The Council' as opposed

to the nearby Church or National School of about the same age which was always

called the 'Nash'. In the 'Infants' the teachers were all women and the classes

were a mix of boys and girls. There was just one vivid memory of a lady teacher

taking a girl in our class across her knee to apply a slapped bottom. We boys

were keenly interested in this event as we felt ourselves to be positively discriminated

against in terms of corporal punishment. A girl about to be disciplined in this

way was unique in our experience and I would like to think it was this uniqueness

which was the cause of our keen observance of the event. But I believe it was

the method of administering the punishment which captured our rapt attention,

for the teacher, an otherwise kindly grey haired lady, proceeded to lift the

girls skirt to reveal a rather worn pair of faded and stained black knickers

with a hole in them. The slight protuberance of pink skin through the hole and

this unsolicited glimpse under a girl's skirt caused a collective intake of

breath rendering us seven year olds helplessly trying to contain breathless

mirth at this unfortunate girl's misery as she endured a slapped bottom. In

the time honoured way of countless generations of heartless schoolchildren the

poor girl was for a long time subject to catcalls of "old peepy pants" - either

from our seeing part of her bottom peeping out of her drawers or a general reference

to their staining. The passing of water in a deliberate fashion did lead me

and several of my friends into the kind of trouble we were definitely not keen

to be communicated to our parents. Receiving any punishment at school was not

to be broadcast by one's self because it usually led to a supplementary slap

by parents who generally believed that the standards of the school reflected

the standards of the home in terms of behaviour or that was the general impression

given. I tended to believe that the behaviour at school warranting the physical

punishment was considered to impinge on the honour of the family in some way

- like the Samurai of the comic books it may have been more honourable to commit

hari-kari rather than admit to the incident which led to our public humiliation

in front of the whole Infants school. It was a particularly nasty schoolmate

who split on his or her friends by bellowing the misdeed and punishment out

as they passed your mother hanging washing on the line. It would, of course,

have been poetic justice if old peepy pants had spilled the beans. This particular

incident was really down to the teachers who, believing in the virtues of self-constraint

refused to let us go to the toilet during lesson times. After all, "Break times

were for those kinds of personal matters." This was in direct contradiction

of the belief of active young boys. Why should we waste precious break times

on the mundane matters of relieving ourselves and thus forfeit the chance to

be in the thick of the playtime hurly burly? This particular day the period

between morning break and lunchtime seemed to drag. Not coming from the Land

of Big Bladders my friend and I were dying to go to the toilet. Kept back for

a few minutes to aid the teacher in some clearing up task we danced about, were

admonished for not going at playtime and finally let free. We hared across the

playground to the only toilets heading straight into the boys' urinal. There

we met with two or three other boys much practised in the art of relieving themselves

in intermittent jets of urine in the same manner as the explosive spurts of

water obtained by squeezing the end of a hosepipe. We joined in blasting the

urinal wall clean of any algae but then raised our sights higher. Now the Boys'

Toilets were red brick built with a sloping roof. Between the roof and the wall

which was about six or seven feet high there was a gap of about two feet presumably

to allow fresh air to ventilate the toilets. It was a sunny spring day and the

girls had the habit of talking, and eating their sandwiches whilst sitting in

the playground leaning against the southward facing walls of both boys' and

girls' toilets. Others tucked their skirts into their knickers and perfected

handstands against these walls. The temptation was too great to resist. We stood

back and directed our jets at the inviting gap. The reaction of the girls was

not immediate as the spots of 'rain' were at first, far from torrential. As

our aim improved so did the deluge and it suddenly dawned on our unfortunate

victims that this was not due to the usual vagaries of the weather. Screaming

with disgust they charged into a teacher on duty, who, seeing the by now dwindling

streams of water dribbling down the outside of the toilet wall, marched unabashed

into the urinal. To be caught in delecto was as frightening as to be caught

at all. The only females to have clapped eyes on our intimate boyhoods were

our mothers or inquisitive sisters. The outraged young lady teacher drove us,

fumbling with our flies, across the yard to the headmistress's office. The trails

of our offence were carefully avoided by gloating boys and girls who flocked

behind us to the school entrance. Ears and rears burning we were tongue-lashed

in front of the whole Infants school and suspended from lunchtimes for two weeks.

Our parents were supposed to be appraised of what was a capital offence and

to foot the laundry bill for the girls' dresses. We kept quiet about it. Strangely

the school did not kick up an almighty fuss - maybe there was no desire for

an admission that supervision of the yard was deficient in that respect. For

a fortnight we subsisted on next to nothing at lunchtimes as we met in the nearby

park passing the time as inconspicuously as possible trying to ignore the resultant

stomach pangs and hoping our parents would never find out. Being the 'top dogs'

of the Infants we experienced none of the kind of taunting meted out to old

peepy and the squatters' rights of the girls to the sunnier side of the playground

were irretrievably forfeited much to the delight of some of the boys who admired

and, I gather, tried to emulate our celebrated bladder control.

To move from the Infants' to the next stage of education - on the same campus

- was something of a shock. The education system was under historic review as

a result of the Butler Act of 1944 and the stages of schooling were about to

be redefined as primary (which could be further subdivided into Infants and

Juniors) followed by secondary schooling of either grammar school for about

15% of the school population or secondary modern school for those who did not

pass the entrance examination known as the 'scholarship' to go to grammar school.

At the time I moved up into the 'junior' stage of my education that part of

the school was still being run as a boys' elementary school where boys between

the ages of seven and 14 received their education.

Upon reaching 14 years of age they left school to take up occupations mostly

in the skilled apprenticed trades or other, unskilled, work. Careers in the

professions and further education tended to be the prerogative of grammar school

pupils who stayed on at school usually until the age of 16. Within two or three

years the changeover would be complete - the remaining 14 year olds had moved

into the wider world and the junior school was inhabited by seven to 11-year

olds. It was during the intervening years of the changeover that I found myself

like all the other seven year olds to be the small fry in a sea of big fish.

All the teachers I came across in the 'junior' stage of my education were

men many of whom had endured life in the trenches of the First World War and

some had served in WWII. They had been young men 'under discipline' and some

seemed to want to impart this experience to their charges with liberal use of

the cane for any and every transgression in and out of school if the latter

came to their notice. They were both feared and respected. If you can imagine

the pressure they must have been under to control classes of boys as large as

40-50 pupils sitting in rows of desks as well as facing change which proved

difficult for some to accept it was no wonder that patience was at a premium.

The cane ruled supreme. This was not to suggest that we lived in constant fear

- in fact, the earlier experiences of physical discipline had in some ways inured

us to the fear of corporal punishment. True, it was best avoided and unpleasant,

but the pain was no worse than having your teeth drilled and filled without

anaesthetic by the glass-eyed Scotsman who masqueraded as a school's dentist

in the nearby newly instituted National Health clinic. As well as being the

sincerest form of flattery imitation is also a great tool of learning.

So it did not take long for us small fry to pick up the requirements of the

almost military discipline which attended our learning and movement about the

school. When the whistle was blown by the teacher on duty in the yard at five

to nine we stood stock still and then formed up in twos in our classes on the

next whistle. The 14-year olds marched into the main entrance and keeping in

step to the commands of, "Left, right, left, right," they marched up the several

flights of well worn stone steps to the top floor. The rest of the school wheeled

about in their forms (known as standards) to follow on in descending order of

age. It was usual for each standard to mark time at the foot of the stairs marching

on the spot and increasing the foot worn indentation in the slab of Welsh slate

that fronted the doorway. It was always an orderly entrance, all in step, and

wheeling left or right into the appropriate classrooms for registration. It

took no time at all to feel a certain pride in being part of such a regimented

system of movement - after all we had been brought up on stories of wartime

service and here we were aping what we thought were the smart barrack square

gyrations of our fathers and brothers. I say it was always an orderly entrance

but I do remember a time when, caught short just as the whistle went, I marked

time with my class of seven year olds only to have the abject humiliation of

noticing and being noticed that my army surplus short trousers were giving off

a strong smell and feeling distinctly uncomfortable. In the kind of humane gesture

reserved for the putting of horses and dogs out of their misery the duty teacher

pulled me out of line and sent me home to change my soiled pants. I was not

the only little boy to have this experience. We just did not have the gumption

to interrupt the clockwork precision which attended the beginning of the school

day. Besides, school toilets were no longer my forte. About the only time I

can remember a teacher offering what might have been interpreted as an apology

for giving me the cane was when I could not stand still in line when he was

addressing me. The conversation, conducted in one-sided decibels went something

like this: "Stand still when I'm speaking to you boy!" "I am standing still

Sir." "You are distinctly moving. Do you have St. Vitus' dance?" "My sisters

like dancing Sir but I haven't learnt yet." "You are being impertinent (I did

not know the meaning of this word any more than I knew who St. Vitus was but

his clipped pronunciation gave me his drift) and you are not standing still."

"But Sir I am standing still it's my shoes." This was too much for him. I put

out my hands as ordered and was promptly caned (we called it 'cut') across both

palms. Gripping both open hands under my armpits in the time honoured way of

relieving the sting I rocked not so much with pain as with the unbalanced movement

of my soles. The distress on my face must have prompted the teacher to inquire

about the relationship between my shoes and my inability to stand stock still.

My closest school mate tried to help. "His shoes are tired Sir." Well, what

he said sounded like 'tired' but it could hardly have been pronounced in any

other way because he knew that, in the ways of so many make-do and mend fathers,

the soles of my shoes had been 'tyred' that is reshod with strips of bicycle

tyre. Stretching and nailing the tyre pieces to the soles could never quite

remove the rounded part of the tyre which lay lengthwise along the soles and

it was this that made it nigh impossible to keep your feet firmly on the ground

and induced a sideways rocking motion. The teacher, broke off from upbraiding

my pal about the absurdity of insomniac inanimate objects - a reference to shoes

and to him - and both exasperated and curious, ordered me to show him the soles

of my shoes. I gingerly gripped one ankle and, hopping uncontrollably on the

spot, smarting from the cuts across my hand, rocked on one foot to show him

the evidence of my Dad's workmanship. He actually hooted with laughter, called

another teacher across but then, unbelievably, told me to congratulate my father

on his initiative and said he might be able to supply tyres from his motor bike

to improve my situation. On top of this back-handed compliment he said he may

have acted a little hastily in his use of the cane but in any case I should

have known who St. Vitus was and thus avoided the stupid remark about my sisters.

The free use of the cane was a harsh motivator. I learnt who St. Vitus was and

many other more useful things like chanting the arithmetic tables from twos

to thirteens without error in order to avoid the cane. At least once a week

the whole school assembled for table chanting. At least that's what we called

it. The headmaster called it arithmetical aptitude. We all had to have arithmetical

aptitude otherwise life would be a closed book to us. Many unfortunates did

not even have a closed book to call their own. They were usually kept down a

standard for lack of aptitude in the teachers' terms. This meant that some standards

contained a few poor souls who had not reached the 'standard' for their age

and were kept down a year. Most of the teachers had given up flogging a dead

horse let alone their hides and hands and they were condemned to be the 'hewers

of wood and drawers of water' as I learnt in one assembly with a hint of religious

flavour. Yes, I had witnessed boys being caned for getting the answer wrong

to such questions as, "What is the product of seven and six? (No answer from

the victim) I shall rephrase that: what are seven times six? This of course

is the same as six times seven." Seeing the myriad of upraised hands in the

assembly all straining to show their arithmetical aptitude the unnerved pupil

stammered out an answer which was inevitably wrong because the head had chosen

a boy who had failed this interrogation last week. A public caning usually of

one or two strokes resulted. In my imagination I could see that at some time

the victims would be seized up to the blackboard and the cat o' nine tails taken

from its bag and applied 42 times across the unfortunate miscreant's back. If

such displays of corporal punishment were intended to encourage the others they

certainly had some effect on accelerated rote learning. One incident that has

stuck in my mind took place in my final year of junior schooling. Having been

warned several times for talking out of turn by my scholarship class teacher

I was called to the front of the class to be caned for persistent chatting.

I hasten to add that I really liked this teacher (Mr Stan Stuckey) who was one

of the old-stagers and had an enviable reputation at getting his pupils through

the scholarship. It was my second year in his class as I had been promoted a

standard (yes you could go up as well as down in this system) at nine years

of age but had been too young to sit the grammar school entrance exam the previous

year. He stood no nonsense but seemed to be all too aware that his pupils, who

were by then a mixture of primary school boys and girls, were the crème de la

crème in a district school which still found that grit could be turned into

pearls. Taking his avuncular mien somewhat for granted I had tried his patience

once too often. It was a wintry day and the caretaker of the school had lit the

coal fires which still existed in most classrooms. The teacher took the cane

out from behind his blackboard and flexed it for use but the ends of the cane

were flayed into strips. To add insult to impending injury the teacher told

me to put my coat on, gave me a tanner (not the cane itself but sixpence!) and

sent me to the local shopkeeper who provided the school with canes. This corner

shop had cornered the market in these instruments of torture and a further twist

was that the shopkeeper still nurtured an outstanding debt from my mother who,

like everyone else, had several grocery items 'on the slate' until payday. Seeing

me shopping in the middle of the school day caused him to remark, "It's good

to see your mother has given you a special errand to pay off what is owing."

Taken aback I blurted out that it was Mr Stuckey at the school who had sent

me to buy a cane for him I added that I was to be the first recipient of its

favours. The disappointment at non-settlement of my mother's bill was replaced

by a wide grin as compensation for my lack of financial fruitfulness. He brought

to the shop counter a rather apt cane basket containing a variety of more lethal

canes. With deliberate and dramatic painstaking he selected and rejected several

canes remarking that Mr. Stuckey liked greater flexibility and length or that

he liked a more open hooked handle. He lovingly explained that Mr C. another

teacher of more sadistic bent preferred the short stubby thicker version, that

Whacker W. preferred a stiff rod-like one and Basher B. liked a thinner, whippier

variety. Generations of schoolchildren including my own father would testify

that, of all the teachers, Mr C. was universally feared when on yard duty. He

carried his short, stubby cane, about the thickness of an adult thumb, in his

coat pocket so that about nine inches protruded on show to all who passed near

him. It was particularly painful to be rapped across the knuckles with it or,

even worse, cut across chilblained hands in cold weather. My father who attended

the same school once told me that after doing this to one young boy during the

first War the boy's older brother, on leave from the Navy, stormed into Mr.

C's classroom and floored him with one punch for, "Splitting our kid's chilblains

with his bloody stick." This rather direct intervention may have had a salutary

effect for a while but by the end of his career he was still wielding his stick

with the same old relish. At last the shopkeeper chose what he called, "The

right kind of cane for old Stan," made an ominous swishing noise as he clove

the air with it, took the proffered sixpence and hoped it would repay his careful

selection for the teacher. I left the shop with the cane carefully wrapped in

brown paper but with the crooked handle left uncovered. There was still about

an hour to the end of school and there was no way I could justify a 10 minute

walk from school had taken all of 60 minutes. There looked like no chance

to delay the inevitable but, perhaps an outside chance that I could be waylaid

and my oddly wrapped piece of shopping forcibly taken from me came to mind.

Rather than walk back by the main road and streets leading to the school I would

take the ever present lanes - those alleyways of noisy games playing and the

alien territory of gangs based in the houses that shared these common routeways.

For once, the Boardie must have had an impact or the cold weather had curtailed

operations for the rival gang members who may all have been in school. I returned

to school unmolested by older boys of the Dick Turpin kind and wondering where

there was a footpad when you most needed one. On entering the classroom there

was a solemn hush. The ritual would begin. The sacrificial lamb had arrived

bearing the rod of atonement. My hands were cold, my tongue dry and my sphincter

muscles tensed. Old Stan unwrapped the cane in a way that suggested he was about

to whisper endearments to a willowy mistress but instead he thrust the end into

the glowing embers of the fire. This sudden and unexpected turn of events gave

me a glimmer of hope that Mr S. had seen the light and was to eschew the ways

of physical correction for eternity. Fat chance. Removing the tip of the cane

from the fire he snuffed out the singed end with his sausage like fingers. Ever

keen to impart knowledge old Stan explained to me and, by implication the attentive

class, that by carrying out this procedure he had hardened the tip of the cane

to reduce the chances of it splitting in the way his previous implement had

done. So the gods of the fire could have saved me my errand of tribulation.

The cane duly cauterized, Mr S. magnanimously gave me the choice of having it

struck across my hands or my backside. No good pleading mitigating circumstances

and partial redemption by being an assiduous runner of errands. Two strokes

were to be administered. My hands were still cold. I chose to have the strokes

addressed to my tightly clenched buttocks. At least there was the covering of

my khaki ex-army shorts. As was the custom I was made to touch my toes, the

hardened end of the cane was scrolled over the seat of my trousers to check

for irregular body armour and the strokes deftly and unerringly laid across

the same spot to maximise effect. At least I was spared the humbug of, "That

hurt me more to do it than it hurt you to receive it." Instead I heard, "You

chose a fine cane there my boy - should see me out to retirement." No pain no

gain. That was the last time I was caned during my primary education.

This kind of correction was part and parcel of growing up in the mid-20th

century. Being able to judge the likelihood of swift retribution for stepping

out of line became second nature. When our finely tuned survival antenna failed

us we were compensated by the pervading atmosphere of family care of which chastisement

was just another manifestation for 'your own good.'

This kind of correction was part and parcel of growing up in the mid-20th

century. Being able to judge the likelihood of swift retribution for stepping

out of line became second nature. When our finely tuned survival antenna failed

us we were compensated by the pervading atmosphere of family care of which chastisement

was just another manifestation for 'your own good.'

I am a Grangetown Boy by Jack Payne

South Clive Street just after the war

| I am a Grangetown Boy Born in Pentrebane When two we moved to Amhurst Street Next to Earl Street Lane The rooms were

dark and damp My father's name was David It was the days of great Depression Men gathered on the Marl |

The Forge Pub across the road was held with great affection Because Mam played the piano there For a welcome penny collection I remember an election then

Our next move was to Clive Empire Day in school

Our future then took a turn |

We played in

street and on the Marl Rode bikes down the subway Swam in Taff Built dams of mud and jumped off Windsor Slipway Then came the war Sid Radford Special Constable

The night of Jan the second

|

| We moved then to Oakley Street On a coalman's horse and cart To rooms dark and dingy Not what you'd call smart.

Our home was then a room |

Vinegar in barrels Carried by horse and trailer Blocks of salt two feet square Sold by Salto Taylor

Pugsley walked the streets of Grange

Sid Lewis the Bookmaker |

The subway under the Ely Bombs fell down, incendiaries too Since I moved away |

This street party in Allerton Street was in the summer of 1981 to mark the royal wedding between Prince Charles and Diana Spencer. The elevated view was from the Elizabeth flats, which have been demolished and replaced by new homes.

|

| LLANMAES STREET - PARTIES THROUGH

THE AGES!

By Rita Spinola

(nee Stevens) When I grew up, was married with three children, my friend Dolly and I decided to run bus outings in the August holidays. We had two for children - to Porthcawl and Weston-super-Mare and in September for the adults. Dolly and I did 13 street parties - each time they got better and better, with bouncy castle, cakes, tea, fancy dress, buffet and dancing til midnight.

Pictured above, top left- a street outing, possibly from 1949

and right of that, the "Elizabeth Inn," a makeshift bar for the Coronation

celebrations. Pictured below left is the VE anniversary party in 1995,

then below centre is a trip to Weston in 1996. Below right is the

most recent street party in 2002 to mark the Queen's golden jubilee

- children and adults wore specially-printed T-shirts with Llanmaes

Street on them.

|

SCHOOLDAYS IN THE LATE 1940s

Dennis Courtney, now living in south

Australia, sends this photo (left): "It would be in the late 1940s

- Mr Whickham's class at the Grangetown Council School. Most of the boys

would be in their late 60s or early 70s now. The building in the background

is the two classrooms they built in the school yard. They used to be Mr

Stuckey's and Mr Thomas's.

Not long after, Graham Ayres sent us this photo of the school's baseball

team (right), with trophies, in Grange Gardens in 1949. He's back row,

fourth from the left. Click on the photos for larger versions - let us

know if you're in the photos and have any memories!

| "GOING OVER THE BORDER" - THE GRANGETOWN TO PENARTH SUBWAY

By Jack Payne

I believe it was in the 1920s that the subway was built underneath the river Ely connecting Grangetown with Penarth Docks. I think it was made to enable dockworkers from Cardiff to access the newly formed Penarth Docks.

Prior to the war our family often frequented the area beyond South Clive Street

leading to the subway because for some time my mother Peggy was the pianist

who played in the Red House pub. Whilst my mother and father, (who played

drums) were in the pub I with my brother and sister played on the slipway

behind the pub.

During the war access to this area was denied to all who but those working

in the area and Special Constable Sid Radford, who had a shop in Paget

Street, was posted there along with one other to police the access. When

the war finished this area along with the subway was opened for public

access. The subway was used as a quick route around the rocky coastline

to Penarth beach and pier. Initially there was some person on guard at

each end of the tunnel, which sloped very steeply from the Grangetown

end to an "S" bend at the bottom and a more gradual rise to the Penarth

side. There was a naked 60-watt light bulb in the roof about every twenty

yards. The ceiling and walls were always dripping with water and when

it was first opened after the war there were plenty of stalactites and

stalagmites. The guards were there ostensibly to stop persons riding their

bicycles through the tunnel. After a few months the guards at the entrances

were removed and youths using the subway took out the light bulbs and

threw them to the bottom causing a loud explosion. For a while the authorities

replaced the light bulbs but as they were continually getting smashed

they eventually gave up. This plunged to tunnel into complete darkness

and at the bottom one could not see their hand in front of their face.

As there was nobody to stop them persons began riding their bicycles through

the subway and as they had entered in daylight they had no lights. Consequently

anyone walking in the subway had to keep a sharp ear for the sound of

swishing tyres as the bicycles would be travelling at a fast speed. Running

along the side and full length of the subway was a large pipe about a

foot in diameter. If one heard a bicycle coming, jumping onto this pipe

was the only safe refuge.

Sundays in Cardiff in the late 1940s were dead as the proverbial Dodo.

Shops, cinemas and pubs were all closed. The only places open were churches

and other places of worship. Then the Marina concert hall on Penarth Pier

opened with live talent contests for singers, comedians and musicians.

When the tide was right, you could walk around Penarth headland from

the subway to the pier. This meant there was a steady flow of teenagers

using this route on a Sunday evening. the term used by the teenagers was

"Going over the border". When the tide was up the train from Grangetown

Halt was used.

Jack's younger brother KEN PAYNE adds his memories of the Subway

from the 1950s: "This in essence was a metal tube under the River

Ely, very often it was in complete darkness.We would venture through the

darkness untill we could see the little halo of light appear telling us

we were nearing Penarth Dock.Once up in the dock you could cross the dock

gates and walk down to the pebble beach. Penarth dock had several World

War Two ships that had been mothballed which carried a great deal of interest

to us.The little pebble beach at Penarth was quite popular on nice summer

evenings. There would be lots of people taking a dip here. One of the

things that I found intriguing then were the metal stairs that used to

wind down from the cliff top,only to come to an end halfway down where

they’d fallen into disrepair. These stairs must have been a hair raising

experience even whilst in good order.When it was quiet we would pass our

time hurling rocks at the cliff face to try and bring it down, we would

be delighted at any small rock fall."

"We would also spend our time roaming around the dock looking for

scrap metal. This would consist of old nuts and bolts, off-cuts of metal

plate and any metal object we could carry. Once we thought there was a

sufficient weight it would be a case of lugging the metal back through

the subway. Then it was down to Bill Ways' scrapyard to see what we could

get. Generally we would be given a half crown or two bob - a pretty miserly

return for half a day dragging metal from Penarth to Cardiff, but we were

happy."

Under the river - the Grangetown subway

ZENA MABBS looks at the Grangetown subway, which ran under the River

Ely from late Victorian times. It's still there of course, if closed off.

Work began on the subway in 1897 using a trench and cover technique

from the Ferry Road, Grangetown end under the river at the same point

as the ferry crossing. The lowest section of the tunnel lies 11 feet

below the river. The decision to construct the Ely River Subway was

made by the chairman of the Taff Vale Railway, Arthur E. Guest. George

T. Sibbering, chief engineer of the Taff Vale Railway designed the subway.

The tender sum was £36,203 submitted by Tom Taylor, a mining quarrying

and civil engineering contractor from Pontypridd. The first cylindrical

section of the tunnel was laid on 5th July 1897 and the last on 15th

September 1899. It was opened the following year on 14th May 1900 by

Mrs. Beasley wife of the railway's general manager, replacing the earlier

rowing boat and steam ferries operating across the river. A toll keeper

collected a penny for each pedestrian but police and postmen were exempt

from charges. It cost twopence for a bicycle and fourpence for a perambulator.

Horses were allowed through but no one remembers the charge. Tolls were

abolished in 1941. The subway carried the hydraulic power line from

the power station to the coal tips at the harbour and a high pressure

water supply to fight fires at the oil storage area. My footsteps returned to the Grange today

With youth renewed I wandered at will

I looked at my hands There is a fantastic website

on the history of Penarth Docks, which includes more details about

the Ely subway and how it was built.

|

Grangetown's front line of defence?

Michael Griffiths, a former Grangetown resident recently sent the Grangetown

Local History Society a photograph of this pill box, off Penarth Road,

asking "is this going to be saved?"

Although Michael lives in Scotland he is a frequent visitor to Grangetown

and to his Grangetown family. The pill box can be found off Stuart Close,

before Penarth Road reaches the link-road fly-over. Michael also remembers

it being used as a bird hide.

Around 28,000 pill boxes were built at strategic points across the UK,

during World War II - sited at places such as road junctions and waterways.

It is estimated that 6,000 still remain today. There's a great website

devoted to the study, record and preservation of

pill boxes as well as a pill

box study group. There don't seem to be any listed for our part of

south Wales, apart from at the old aircraft base at Llandow in the Vale,

so the society is going to contact them.

THE BIRTH OF SOUTH CLIVE STREET

By Jack Payne To facilitate the move we used a handcart hired from the Gas Works, the type

used for carting coke. All the furniture we owned was piled onto this handcart.

For the first few weeks of living there we slept on the bare floor boards. At

that time along the whole length of the street houses were in various stages

of construction. Some were at the basic foundation stage, others were half built

or completed but awaiting interior decorating whilst about 20 were already occupied.

No. 81 was a three bedroom semi-detached house, the other half - number 83

- was still being completed, with interior doors and the like still to be fitted.

The other side of us, no 79, was still at the first level stage of being built

whilst directly opposite the family of O'Connors - children Billy, Dolly, Eddie,

John and Betty had been in occupation for some months.

Having moved there from living in rooms this was an area of wonderful excitement

for boys of my age and there were many of them. At first there was no watchman

on the site and as Cowboys and Indians were the in thing bows and arrows were

required. The site offered large quantities of wooden laths and string enough

to supply all the boys in Grangetown.

At the same time, as families moved in they helped themselves to sand and cement

to build garden paths for their homes. This soon resulted in a watchman, Eli,

being employed to cover from 5pm until work started the following day. The houses

were being finished at quite a fast rate and families were moving in daily.

No1 the Vernacombes, Graham later played as goalkeeper for Cardiff City; at

2 the Olsens, withson Alfie; No 4 the Buleys,Tom and Leon; 6 Barnets Alan; 8

Fearnley, no children but Charlie helped to run Cardiff Gas Boxing Club. 10

Lovell, Alan, opposite side Kazeras, Blakeys, Imperato, Leonard, Ryan, Shaw,

Preece, Sanders, back odd number side Lucas, Graham, Nicholas, Graham, Grady,

Parfit, Morgan, Parsons, Corner of Beecher Avenue, Bulpins Trevor and Vera,

Balch, other side O'Shea Paul, 63 Attley, (inserted by Emery family:)

65 Emery. "We moved out of South Clive Street in 1950 to 5 Ludlow Close. Uncle

Ned Rodd used his horse and cart to help move us all. My aunt Thelma Adams lived

at 120, with husband Albert and son John." 67 Rodd, 69 James Mavis, 71 Gill,

73 Fearnley Craig , opposite Cornish, Greedy, Perkins Malcolm and Cedric, Coles

Josey, O'Connors referred to above, James, Shelley Sylvia and Maureen, Bevan

Teddy, Stubbs Jean, Pearce Ronald, back on odd side 75 Parry Gordon and Dennis,

77 James, 79 Alloway Sylvia, Dorothy, Pam, Valerie, 81 Payne, 83 Chiplin Gladys,

Irene, Thelma, Sylvia. They had an evacuee named Rene Grinewald during the war.

85 Born, 87 Evans, 89 Swan, 91 Leigh, Maureen, they left and a family named

Hall Raymond and Tom moved in. 93 Young 95 Saunders Dennis, 97 Williams Chrissie,

99 Davis "Curly" 101 Andrews Billy he had six fingers on one hand and Stanley

"Ikey". Opposite side Guppy Graham, Johannison, Roach, Binding Barbara, Bellamy

Celia, Batten, Kennedy and others I cannot at present remember. These were the

first people to take up occupation between 1937 and 1940 many families later

enlarged by having more children.

When all the houses were finished and occupied

early 1939 they built walls all along the fronts of the houses and topped these

walls with a wrought iron fence about 18 inches high. Each house was also provided

with a wrought iron gate to their front path.. The pavement was laid in large

concrete slabs and the area between the pavement and road about five feet in

width was laid with turf. No trees were planted at that time. Soon after the

war started the gates and wrought iron fences were removed as scrap for the

war effort.

As the families moved in and removed the builders rubble from their front gardens, the majority laid the front garden to lawn. Turfs of sea grass were dug from the tide fields. These turfs made a lawn of strong wearing really tough grass. I know it was tough because it was my job to cut it with a pair of shears. No lawn mower in those days.

The depression era of the 20s and 30s spawned a generation of hardened street wise kids in Grangetown. A large number of these were domiciled in South Clive Street already toughed to withstand the shortages and perils of the coming war.

The building of the houses in South Clive

Street began in 1937. Our family then consisting of Mam and Dad, sister Hazel,

eight, two-year-old brother and myself aged five, moving into number 81 in the

spring of 1938.

VE Day celebrations at the top end of South Clive Street in May 1945.

Pic: Jack Payne.